can a poem save a life?

to suggest that a poem can save a life is to first imply an understanding of what constitutes a life that requires saving.

but first, a confession:

something a little different this week.

i wanted to thank you.

yes, you.

yes, all one thousand and twenty four of you.

so: thank you.

dear little voice,

to suggest that a poem can save a life is to first imply an understanding of what constitutes a life that requires saving.

this question itself demands a necessary distinction: one cannot mistake the process of saving a life with that of saving a body.

whereas to save a body has historically involved simpler solutions such as its withdrawal from the trajectory of a moving vehicle or its provision of a pill or intravenous device, what constitutes the saving of a life has reached virtually no consensus amongst otherwise intelligent people for centuries.

far from the fields of mechanics and medicine, the duty of saving a life— and its associated methodological complexities— has historically been delegated instead to the field of religion. religion’s general procedure for saving a life is much less concerned with the body, and more-so with the inner life– or, to use its more specific terminology, the soul.

although there is methodological disparity from religion to religion regarding what actions must be undergone exactly in order to save a life, in general religions seem to insist upon a two-fold procedure primarily hinging upon a life’s relationship with the object of sin. this procedure generally involves:

cleansing the life of pre-existing sin

deterring it from future sin

studies of what exactly constitutes a life– or a soul– and of what constitutes sin are therefore essential to answering the question of whether or not a poem can feasibly save a life at all.

the existence of an inner life is not widely contested.

of course, no surgeon has ever opened up a brain and found a tidy nest of thoughts— yet the reader will find that empirical proof of an inner life is available to them at any given moment by way of rigorous experimentation.

one might, in order to garner this assurance, simply sit in silence long enough to experience the mysterious emergence of a world both clearly inhabited but totally unrelated to that which their body is experiencing: the eyes close, and whilst the body remains at the chair, or by the tree, or on the bed, the life returns to the soil of a childhood garden— the smell of a lover’s neck; kinder breezes, the sounds of flutes—melodious and sad— the cries of vendors in long-gone markets, hours of ample love and troubled words, sweet mouths, a long-forgotten street at midnight— buried in the contours of memory: that city of ghosts where storage is easy, but retrieval is hard.

we have noted these findings. it seems that despite the immediate availability of a body and all of the outer attractions of the world, there does exist somewhere within it something quite satisfying and beautiful in itself: some aliveness without the contours and limitations of a body.

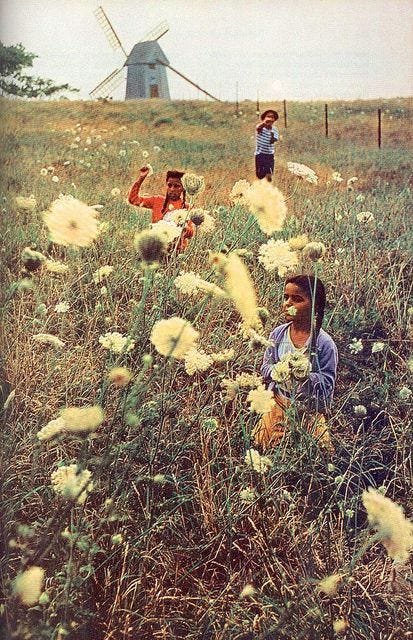

Path Through a Field of Bluebonnets, Robert Julian Onderdonk

the mystery is not so much that these two dimensions exist– the apparent outer body and the mystery of the inner life– but that the reader reading this is not either. rather, they are the thing suspended between them. they are merely a space in which both worlds meet— as if the reader is a meeting point, or the threshold between two worlds: the world of the body, and the world of the life.

even the briefest of consultations with any religion will confirm to the reader that it is a dangerous thing to be in possession of this life at all— far more-so than it is to have a body, which according to our findings seems instead to be only a life’s passive instrument. and whereas the mishandling of a body results in what at worst could be described as a very long sleep, the mishandling of a life results— according to the literature available— in nothing less than eternal persecution.

if you have a life and a poem can save it, then it must follow that poetry, for this reason, is immensely important. but if we are to pursue at all the question of whether or not a poem can save a life, we must first define that which threatens it in the first place.

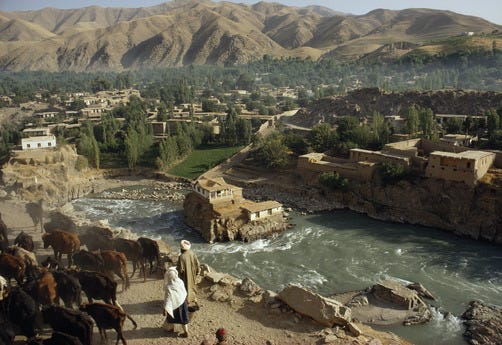

Serpentine trail wends it way through the Cerro Verde mining region, Peru, Bobby Haas.

sin is an interesting word not only as a barometer of a soul’s safety, but also linguistically.

the word itself is an English word for the Ancient Greek ἁμαρτημα. Ἁμαρτημα is, in turn, derived from the verb ἁμαρτανω, which translates roughly into english as the verb: to miss the mark. Ἁμαρτανω also shares its roots with the Latin peccare, meaning to stumble, trip, or falter. again in Hebrew we see the verb חטא used for sin— also meaning to miss the mark.

etymology provides us with a curious interpretation of sin: not one of shadowed evil and premeditation, but one more closely related to a bumbling misstep— a product not of malicious intent, but of a certain blindness or lack of orientation that results in simply missing the mark. it is the kind of failure that can only result from a total absence of direction.

as Eckhart Tolle writes: just as an archer who misses the target, so to sin means to miss the point of human existence. it means to live unskillfully, blindly, and thus to suffer and cause suffering. again, the term, stripped of its cultural baggage and misinterpretations, points to the dysfunction inherent in the human condition: each of us carry very sharp arrows— and are, for the most part, gesturing vaguely with them in the dark.

what, then, is made of the oriented life? what, then, do we lose when the body remains operational, but the aliveness inside switches off with the ease of an appliance? and what then is made of the sorry body that has lost its life, but must go on without its primary animating force?

it is a dangerous thing, it seems, to have a life.

if a life in jeopardy is characterised as lacking orientation, it follows then that that which has the power to save such a life is a tool of orientation.

the French philosopher Malenbrache argued that attention is the soul's natural prayer. it comes as no surprise then that the word religion comes from the Latin verb relegare: to focus the attention or to move carefully.

all religious praxis are exercises of attention. by extension, all methods of worship are praxis of attention. churches are sites of attention. temples are sites of attention. palms that come together. foreheads that touch the earth. mats like tongues in their abrupt mid-air unfurling.

if a poem is to be empirically capable of saving a life, it holds that in order to do so it must be akin to a tool of orientation— not necessarily a destination in and of itself, but rather a suggestion toward a governing path: a gesture in the right direction toward the mark being missed in the first place. a call to attention. a compass. a hand. a match struck in the dark. quiet, the poem whispers, listen, now, to the sound of it– like rain, like scintillation, the tearing of oranges, a coin in a well. the thing that falls to its knees inside of you. now: follow it.

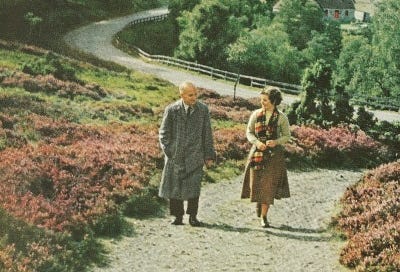

Friends walk amid the heather growing in Scotland, National Geographic, July 1956

in his oft-quoted poem Asphodel, That Greeny Flower William Carlos Williams writes:

It is difficult

to get the news from poems

yet men die miserably every day

for lack

of what is found there.

if our methodology so far is accurate, a life saved is a life with an oriented attention.

poetry asserts its relevance to this by serving as a sovereign compass for our engagement with the world. read a poem and listen for the covert interior echo cast— the certain resonance in your muscles and nerves, identifying you to yourself, beckoning you to an imaginative elation with the otherwise ordinary.

the question that remains in this essay is this: what exactly is the location that the poem gestures toward; this liminal space without which people die every day for lack of what is found there?

whether it is Wendy Cope writing about an orange, or William Carlos Williams about a red wheelbarrow; Ocean Vuong allowing that time spent lonely is still time spent in the world, or Franz Wright on the windows that illuminate your little walk home and on the thousands of people behind them who must be dying to welcome you into their small bolted rooms, to sit you down and tell you what has happened to their lives; Galway Kinnell insisting that you trust the hours because haven’t they carried you everywhere up until now, or Phillip Larkin demanding that we must be careful with each other, we must be kind, while we still have time– it seems to me that all poetry is united in one thing: in its insistence upon directing our attention; in its unyielding reverence for the oft-overlooked but miraculous minutiae of our lives; a demand for a radical politic of vulnerability: an acknowledgment that we are real human beings with real raptures and real ascendancies carrying real lives with the real ability to harm or help one another, and the gift of witnessing oranges and red wheelbarrows whilst we do it– and that we must be awake to this fact, remain alive to it– and perhaps a little vulnerable to it, too.

this is how poetry directs us: not with the certitude of answers, but with recognition; with delight. this essay is not an endorsement of a utilitarian aesthetic— as Auden wrote: a poem does nothing— rather, it is one interpretation of our pleasure in poetry as a celebration of life, as an adventure that rejoices in the very act of being alive— and just maybe saves us in the process.

when I advocate for poetry it is not because I simply like beautiful things. there would be easier and far more socially acceptable ways to support that movement.

later in that same poem, William Carlos Williams writes:

the poem

is complex and the place made

in our lives

for the poem.

it is no secret that we are creatures for which the unknown causes great discomfort. from what I have been able to surmise, people think they do not like poetry because in a world so delighted with clean answers, poetry does not offer clean answers. this is because poems are inherently complex creatures that exist in only the most complex spaces of our lives. you can’t tie a rope around a poem and expect the tether to hold. who are you to bring a question to its knees?

a poem will not take you to the place that saves your life and dust off its hands. but a good poem— a really, really good Poem— will nod in the right direction.

i speak to many people every day who ‘hate poetry’ or ‘don’t get it’; who wrinkle their noses in either apology or alarm when I say those embarrassing words: me? I’m a writer.

and in a way, they are correct– they don’t ‘get’ it. and they never will. and i never will.

the poem resists comprehension because it resists control– by way of syntax or by way of interpretation. what Poetry give us is not an answer to our predicaments and uncertainties, but instead a radical faith in the beauty of our questions. this faith is a faith active in its orientation; an orientation of verbs: of questioning, exploring, experimenting, experiencing, walking, running, dancing, playing, eating, loving, learning, daring, tasting, touching, smelling, listening, speaking, writing, reading, drawing, provoking, emoting, screaming, sining, repenting, crying, kneeling, praying, bowing, rising, standing, looking, laughing, cajoling, creating, confronting, confounding, walking back, walking forward, circling, hiding, and seeking with a reverence for the mysterious impact and unequivocal beauty of what exactly it is you are experiencing and exacting upon the earth in your most brief of hours here.

when I advocate for poetry as baptismal, as a sacred place, as a touchtone, as a compass, and as a site of salvation, it is because it is where ongoing conversations with our evolving selves unfold. it is because in a world with enough advocacy for certitude and clean answers, what we need now more than ever is a space that deliberately indulges in our paradoxical limitlessness as mortal creatures.

it is because we need a space that exists between body and life– and, quite possibly, creates the bridge between them. it is because I have had enough of my pride; of my childish preoccupations with certainty, with my lust to be correct. it is because I want to see the first snow of winter and cry— and choirs and seashells and terrible sweaters and cigarettes and magnolia trees too. it is because i want love to be important because i don’t know what it is, not in spite of that— and beauty and succour and bliss too. it is because i want so desperately to notice all of these things— and when I do, I want something to fall to its knees inside of me and weep.

when it does, I don’t want to ask why. i simply want to swim in it as if in a sea— without the contour and limitations of my body.

it is because I want these things to be important that I want to remember them. and it is because I want to be remember them that I want to keep a record of them. and when I do, I want the record not to pander to my human practicalities and record, say, a bus stop, but to insist that that bus stop there was once a coral reef, and where that sign that reads DEPARTURES stands, a torrent once roared, there were frozen rockslides– meteorites the atrocious colours of lunar sulphur.

if a poem can save a life, it follows that the experiment must be completed.

Toni Morrison famously wrote that “the grandeur of life is the attempt, not the solution... it’s only about behaving as beautifully as possible as one can under completely impossible circumstances.”

the grandeur of life is the attempt, not the solution.

poetry does not disguise itself as a solution. it will not take you to the place that saves your life. but it will awaken you to the sheer aliveness of the attempt.

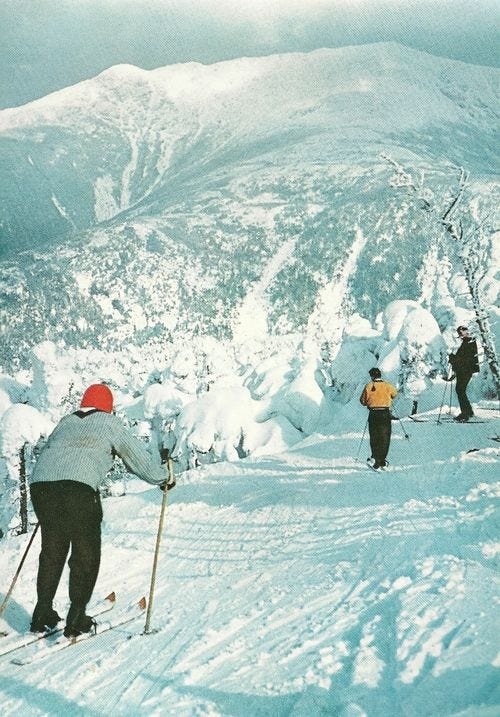

Skiiers on Mount Lafayette, New Hampshire National Geographic, February 1959

i love poetry because poetry makes me very careful. i love poetry because it makes me pay attention while i still have time.

i love poetry because i want a part of all of us not to die, to instead be passed on– whether as wisdom, as play, as goodness, as touch across time, or as memory. i need to know that the best of us will be celebrated in words and therefore won’t be left behind. i need to know that sentences won’t be reserved only for news of kidnappings and killings– but also for oyster shells and sawdust restaurants and skies and oranges and red wheelbarrows and time and insects and dirt and love and even, for a time, me and you.

we cannot fix everything. we cannot be certain of anything. but I know, at least, what it feels like to know that the things i do want to save are important, even if i don’t completely understand them.

yes, this inner life is shy of visitors. it is not a straight talker. but the point of getting close to it, from what I can surmise, is to pay attention– to not seek the easy way out. to search for beauty like you would a bruise– to keep pressing down until you find the point that feels something.

there is an italian phrase: ‘gazofilacio’ meaning: treasure chamber of the mind. it is the word given to the ragged little store of poems you carry inside of you, wherever you go, always intimately rekindling and redirecting your attention.

as i grow older i have come to recognize the precariousness of our passage. the difference between surviving and sinking is not so different, it seems— but to insist on being alive often comes down to what we have managed to retain in our grip, to store away in our gazofilacio, this treasure trove of the mind.

find these pieces. keep them close. they are what might just save you— not because they protect you from the questions and difficulties of life’s passage, but because they demand of you a certain delight in them.

unlike most mechanisms of salvation, poetry will likely not find you in a plume of smoke at the end of the story. instead, you need to go out with lanterns, searching, while you still have the time. to engage in the hunt.

what buoys us are these fragments we keep— these private significances, unique and inexplicably vital. what resonates with you may hold no weight with another; these things are not tied to simple answers. but whatever holds meaning for you—no matter its form or essence— i say, is important, and so it is crucial to seek it, to secure it close, to pursue it relentlessly. these are the pieces, the relics, i have amassed against my own ruin.

so please, i urge you, to read a poem. you can read a loud poem, or a quiet one. one that claws at you or another that places its muzzle in your lap. one that rains or one that, like the earth, is simply absorbing.

you do not need to get to the meaning of it. but i do promise you that even if you leave the page shaking your head at the inimitable waste of hours spent contemplating a red wheelbarrow or a stone, the world will begin, throughout the next few days, to slowly change shape— suddenly a bird, a lake’s honest reflection, a woman chewing gum at a traffic light, the haze of mid-morning bell flowers all revealing themselves to you like matches struck in the dark.

this is the sound of it– like rain, like scintillation, the tearing of oranges, a coin in a well. the thing that falls to its knees inside of you. now: follow it. this is the sound of you creating your gazofilacio. and what are we, if not what composes what is inside of us?

perhaps in that way, when we follow its directions, we are saving poetry itself as much as we are saving our own lives.

these fragments may not be able to save your body when that final day arrives, but they may just save your life.

it follows, then, that you at least perform the experiment.

love,

ars poetica.

thank you.

little voice: it is my belief that Poetry is a human birthright. it is for this reason that my work will always be completely free, but it takes considerable Time and Love to give to you each week. if it has brought you something, please consider buying me a book so that I may continue to tuck Words in your pocket:

deeply human, deeply touching, and so profoundly beautiful. thank you for sharing these thoughts with us, for planting these seeds, thank you.

Thank you.

Poetry helps to remove the cataracts from our eyes.