welcome and thank you, paid subscribers.

these will be a different sort of letter— something more casual— in which i will focus on one poem. at the end of each month i will invite everyone to share their own thoughts, intuitions, and experiences with the poem at our monthly poetry circle, held on Zoom. i will also tuck a prompt in your pocket at the end of these letters— drawn from the poems we study. i encourage you to bring your poems to our circle so that we might share them with one another.

our first circle will be held on:

13 April 6pm MDT (Denver Time)

13 April 2pm HST (Honolulu Time)

14 April 10am AEST (Melbourne, Australia time)

the link to the poetry circle is available at the bottom of this newsletter. the circle will be recorded for those who cannot make it. if you have any questions regarding what time the session will be in your time zone, or about anything at all, please feel free to reply to this email.i so, so hope you can make it.

dear little voice,

upon my first encounter with Inger Christiansen’s alfabets i was spellbound. vivid, mysterious, and sensuous, i was suddenly amazed at how anything in the world could exist at all.

you can read a complete version of the translated poem here.

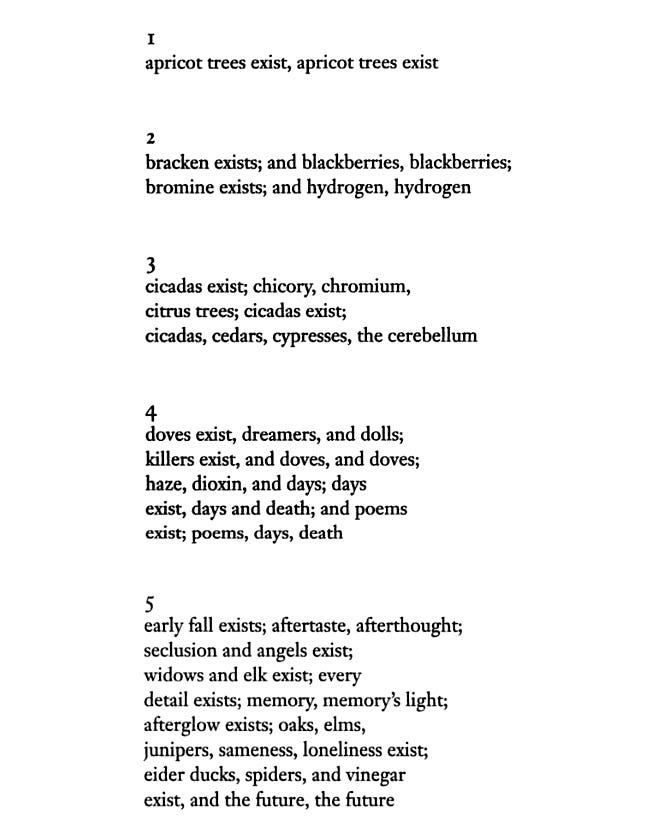

an excerpt from Inger Christiansen’s alfabets.

but why does this poem move me? i am troubled by it as much as i am in awe of it. why, when i first read it, did it begin to grow inside of me like tissue or bone?

at first glance, it is perhaps difficult to justify that this poem is a poem at all. after all, it seems to be more litany than verse, more list than literature.

apricot trees exist. bracken exists.

and blackberries.

blackberries.

of course these things exist. but why is it important to confirm this with language? why should this fact be written down at all? why does it move me so that it has been?

doves exist, dreamers, and dolls;

killers exist, and doves, and doves.

it is a list. and yet these words, repeated like a mantra, seem to crystallise a most elemental truth.

apricot trees exist.

photographer: scrivo

in her essay “It’s All Words” Danish poet Inger Christensen offers a very simple, yet possibly unexpected, statement about the nature of poetry:

“But poems aren’t made out of experiences, or out of thoughts, ideas, or musings about anything. Poems are made out of words.

It’s through our listening to the words, to their rhythms and timbres, the entirety of their music, that the meanings in them can be set free.”

this particular essay happens to be about her collection alfabet— the book-length sequence of poems from which our first excerpt is from— in which each piece builds on, rearranges, revisits, and expands upon what has come before. it is project that began as process of collecting words and, as she was foraging through the dictionary, she happened upon what would become the form of the poem itself: the Fibonacci sequence.

and blackberries. blackberries.

the Fibonacci sequence is a mathematical concept first introduced to the western

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Ars Poetica to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.