one might still offer even to the betrayed world a rose.

living seems to me to be something like this— less an act of figuring out 'how' and more an act of realising 'oh yes'.

dear little voice,

Annie Dillard tells a story in The Writing Life of a well-known writer who was collared by a university student asking: “do you think I could be a writer?”

“well,” the writer said, “i don’t know… do you like sentences?”

the writer could see the student’s amazement. sentences? do i like sentences? i am twenty years old and do I like sentences?

the writer thought: if the student had liked sentences, of course, he could begin, like a joyful painter i know— whom when I asked him how he came to be a painter, said, “i like the smell of paint.”

i woke up this morning with a most scandalous desire to simply be moved.

you see, i may not know much, but i do know what i love.

this small fact has saved me on several occasions.

we are accustomed to the idea that artists work with divine material.

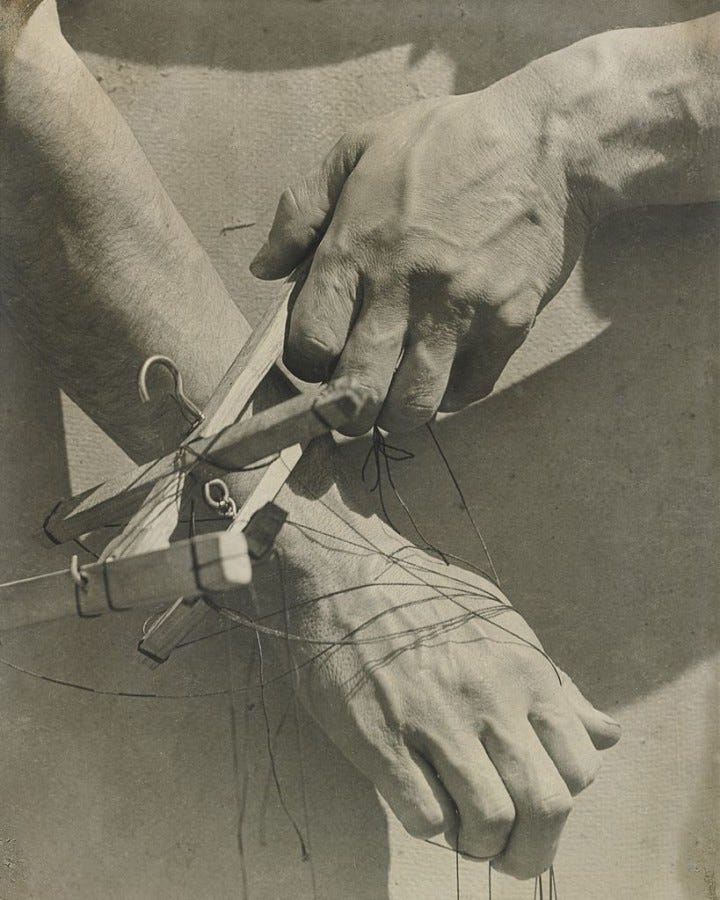

but as we spend our little lives talking, moving, inventing, imagining, hoping, dreaming, frightening ourselves, remembering, forgetting, observing, making, and simply being, we share in this same material— in sentences, in hands, in lines, in colours, and in bodies. we share with the writer when we ask someone to please pass the salt-shaker, with the dancer when we cross a busy street, with the artist when we arrange flowers by the bedside table. but inside of these same ordinary atoms, the artist is quietly digging about in the earth of the everyday, going out with lanterns searching, running their hands over the contours of each hour, probing for the thin places among them.

these thin places are both seen and unseen, known and unknown, imagined and unimaginable, where a door in the shape of your willingness toward it emerges between this world and the next and is left only briefly ajar— a world where time slows to the ripening pace of melon blossoms, ocean foam and gazelle time, where they may breathe in the beautiful and the invisible and their bodies may become its instrument.

heaven and earth are only three feet apart, the ancient Celtic proverb goes, but in the thin place that distance is even smaller.

After Hours Jam, Monterey Jazz Festival, Cannery Row. Fred Lyon, 1958

in thin places, the old words say, the barrier between our world of Facts and the next world of Poetry becomes porous, penetrable, whisper-thin. in these places, certain invisible things— like music or love or memory or art—become suddenly visible. barriers between the you and not-you, the real and unreal, the worldly and otherworldly, dissolve.

in old Celtic stories, the thinnest places were always unruly landscapes and wild places, places overwhelmed by themselves; slit by lightning, crowded by jungle and flowers and green rivers and the ripples of a hawk, places tangled as memory or hair; places like the heaths of Connemara, a place so austere and so ancient, so full of forbidden twists and hidden places and thousand year old pivots and corners that, walking among its unruliness, it seems only natural that one might part a fern or pass a corner and walk headlong into another reality.

you have not walked in Connemara but you have been to thin places. you know them intimately. they are the places where air seems to accumulate around your plain content in a deep, dreamy silence, soft and dense as powder, that has you look at everything closely, even the things that cannot be looked at, things like the air, like the breath coming off of a lover’s body, at the scents of flowers through an open window, at the sounds of little pigeons cooing and scratching at the white dirt. they are the places where you have in secret pocketed little corners like these ones, small pieces of your pleasure left lying around that can be collected and stored, because a part of you understands that there will come a time you will need to know you were here, alive, now. and so you take them with you, into the thicker places, and the people there never even notice that you carry these corners with you always—they are so light and so easy to hide.

An amateur orchid grower works in the window of his greenhouse in Silver Spring, Maryland, April 1971, Gordon Gahan.

these thin places can be found in real, secret worlds swathed in magic— places like Connemara or the hills of the Himalayas or sun-stoned beaches and grief and fury and joy and love— but they can also be humble and intimate: they can be found in dive bars, beds shared, hospital rooms, telephone calls, lonely walks. they follow no rules. they appear and they disappear. they come and go because they are reveal themselves only to your attention.

the poet William Stafford writes in You Must Revise Your Life: “an artist is not so much someone who has something to say and the skill to enable the saying— no, an artist is someone who has found a way into a process that will bring about things to say that would never have occurred to somebody to say had the process not been entered in the first place.”

i like to think of this process as being one of searching for those thin places— of the elemental delight of being acutely and intricately attentive to whatever is available to you here and now.

when Pablo Neruda first found a thin place, he wrote:

something ignited in my soul, fever or unremembered wings, and I made my own way, deciphering that burning fire, and I wrote the first bare line, bare, without substance, pure nonsense, pure wisdom of one who knows nothing, and suddenly I saw the heavens unfastened and open, planets, palpitating plantations, shadow perforated, riddled with arrows, fire and flowers, the winding night, the universe.

when i speak about thin places i am speaking about places where the retrieval of these unremembered wings is possible— of holy places away from the mellow practicalities of the world. places that re-awaken the imagination with a gasp. places so saturated with life that you want to possess them forever; places that lend themselves to transformations both epic and intimate— in the form of poems, dance, music, colours and lines. in the form of delight. in the form of gentleness. in the form of great and tender lives.

this life gives us only so many hours and how we spend them, i worry, is on concerning ourselves with how we spend them.

the very question of what they are trying to make of themselves sounds quite absurd to most artists. in fact, i have never met a true artist who was working towards anything— yet, at the same time, they are all willing to devote their lives to it: to this mysterious seeking, this furious presence, this devotion to a kind of being-in-the-world, a perpetual delight in what fragments of it are afforded to them, a pocketing of these fragments, a love for them so invulnerable and so profound that they render it permanently in prose, in acrylic, in the arch of a spine, in music, in flowers, in rhyme.

these artists work of their own volition. they are not creating in order to make of their lives stories, idols, or legends. this is not why Delacroix, Lispector, Baldwin, Morrison, Géricault, Courbet, van Gogh, or Gauguin worked; nor is it why any other artist of the human era has ever worked. they have, however, loved sentences. they have loved the smell of paint. they have loved the brilliance of their own bodies and the rise and fall of a tulip’s stem. they have loved the sheer, available material of their lives— of love and insects and fruit and sin and beaches and disappointment and snow — or at least saw in it something worth fighting to keep alive.

Albert Camus, from “Jonas, or The Artist At Work”, Exile and the Kingdom: Stories (trans. Carol Cosman)

Delacroix believed in what he called ‘the beautiful’; Cézanne in his ‘petite sensation’; Van Gogh in his ‘humanity, humanity, and again humanity’. these artists had different visions for their work, yes— but each of these visions sprang from the same kind of conviction: they fought because they were in love with life and because they believed in it, so much so that they believed it was worthy of every second of their study of it— studies that comprised— and continue to comprise— entire lifetimes.

they saw beauty— or the possibility for it. they saw delight— or a possible path through the dark towards it. they saw the doors to thin places. everything else they made were only attempts to give you the key.

Roberto Burle Marx, a Brazilian landscape architect (as well as a painter, print maker, ecologist, naturalist, artist and musician) whose designs of parks and gardens are remembered now as being innovative as they were simply delightful.

how do we fight for beauty; for the things that bring joy, for sentences and the smell of paint and for sounds and for bodies and for colour and for light? in what ways are we ambitious about this?

the question here is not did you fail or did you win, did you create the right things and were they good and were they beautiful and did people hang them on walls or talk about them in hallways and at parties. it’s: were you ecstatic while you still had the time to be?

“one might still offer even to the betrayed world/ a rose.”

- Zbigniew Herbert

when i hear the word life i usually jolt, because the easy spring of its singular syllable makes it sound far more simple than it is.

we are so used to using living for everyday purposes that it takes a little extra nudge to treat it the way a writer would treat sentences, or a potter would treat clay, an artist: colours or lines, a dancer: a limb or a foot.

the difference between the artist and the non-artist, between the lawn-cutter and the gardener, between the dancer and the walker or the whistler and the musician, is that the former believes in something the latter doesn’t: they believe in thin places, and they fight to prove their existence to others. writers, poets, people who are in love with the available material of their lives leap into it as though it is a grand experiment in what they can offer it, rather than imposing upon it the job of delivering a brief for an argument for their own existence.

the philosopher Wittgenstein wrote something along the lines of: in order to do philosophy, one doesn’t learn how to do philosophy, but rather one learns that one can do philosophy.

living seems to me to be something like this— less an act of figuring out how and more an act of realising oh yes.

this permission is buried so deep within the hidden pockets of our lives that most people— unless they are going out with lanterns every day searching— won’t realise how trivial, how small the signals buried in everyday moments are that propel us forward and into the thin places.

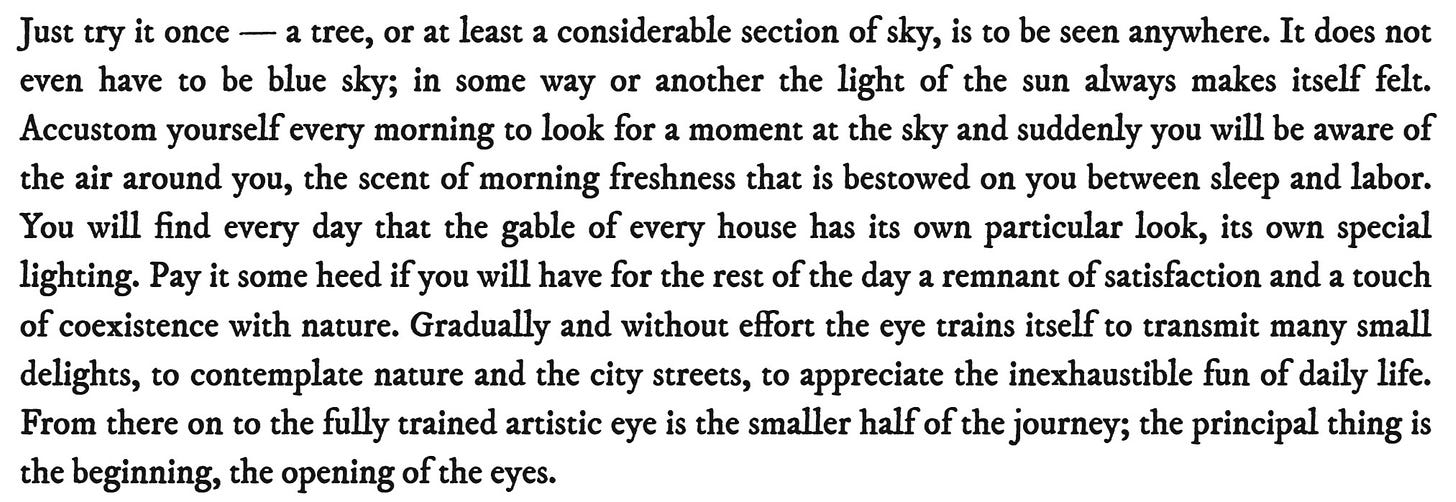

but i want to talk about delight and i want to talk about how generous it is; i want to talk about genius and i want to talk about how easy it is. here, try it once: look as much and as hard as you can at absolutely anything and delight in it all and see how that goes. why not? be clumsy in the right direction. this is your first work of Art: your eye like a new moon, slender and barley open but the first prayer that opens you to faith.

as Herman Hesse writes in his wonderful essay collection My Belief: Essays on Life and Art:

Herman Hesse, On Little Joys, My Belief: Essays on Life and Art, 1973.

these moments will not be chronicled in history or written in books or upon cemetery stones. but if you have held close to you a poem, been kind to someone, enjoyed the certain call of a bird or the slant of light in early spring— well, then these things will be those that one day live in your place.

be an artist. let the material of your life take you, and it will certainly take you to unexpected places. i promise something soon will strike you— a haze of butterflies, a beautiful stranger, the call of a yellow-wren. allow yourself to be guided by the successive experiences of living. cling to these good, good things. you will find those delicious thin places. they will lead you again and again to things you have wanted all your life, but didn’t ever realise you knew you wanted: to ease, to grace, to gentleness, to awe.

here, look down: there is the hand you use. it looks to me almost like van Gogh’s. look closer, yes— he had five fingers also, and Baldwin’s first was also shorter than the others. Lispector’s too had that same moony lilt between forefinger and thumb, and when turned over to face the sun, Neruda’s also dipped to reveal a shallow palm. your hands are as much hands as any of theirs. your eyes, even. your life.

am i important? certainly not in the ways many of us would like to be. will i be forgotten? entirely and without exception. the writer loves sentences. the painter loves the smell of paint. i think i would like to die doing something utterly mundane: sitting on a park bench observing the coming of ducklings in spring, their reticent warble, the measured sway of waterlillies behind them. or listening on as a stranger sings aloud to themselves from a train station platform. or feeling the pleasure of taking off my shoes and rubbing my feet together beneath the table. maybe, just for a moment amidst life’s tiny fragments, i will feel too that i was a fragment, a little slither of humanity who usefully filled a space, however small, for however brief a time.

i hope in that moment waiting for the train to arrive i feel it: lightning hot, a whisper quiet but undeniable all the same: that thin place— the only border between myself and what is worth looking at at all, disappeared.

and then i will step forward.

love,

ars poetica.

little voice: it is my belief that Poetry is a human birthright. it is for this reason that my work will always be completely free, but it takes considerable Time and Love to give to you each week. if it has brought you something, please consider buying me a book so that I may continue to tuck Words in your pocket:

Inger Christensen, from “5,” Alphabet (New Directions, 2001)

"Creativity is a fundamental aspect of being human. It’s our birthright. And it’s for all of us. Creativity doesn’t exclusively relate to making art. We all engage in this act on a daily basis.To create is to bring something into existence that wasn’t there before. It could be a conversation, the solution to a problem, a note to a friend, the rearrangement of furniture in a room, a new route home to avoid a traffic jam. What you make doesn’t have to be witnessed, recorded, sold, or encased in glass for it to be a work of art."

An excerpt from Rick Rubin's book The Creative Act: A Way of Being. It is the most profound text that I have read concerning art, possibly in the way he shows its availability to all.

Thank you for your writing

Today, April 8, 2024. I had no words to describe.

“…in these places, certain invisible things— like music or love or memory or art—become suddenly visible. barriers between the you and not-you, the real and unreal, the worldly and otherworldly, dissolve. “

“…heaven and earth are only three feet apart…”

“…but in the thin place that distance is even smaller. “

Watching the total solar eclipse in the path of totality. These might be some of the words I’m looking for. Feels as though it might just be a “thin place”.