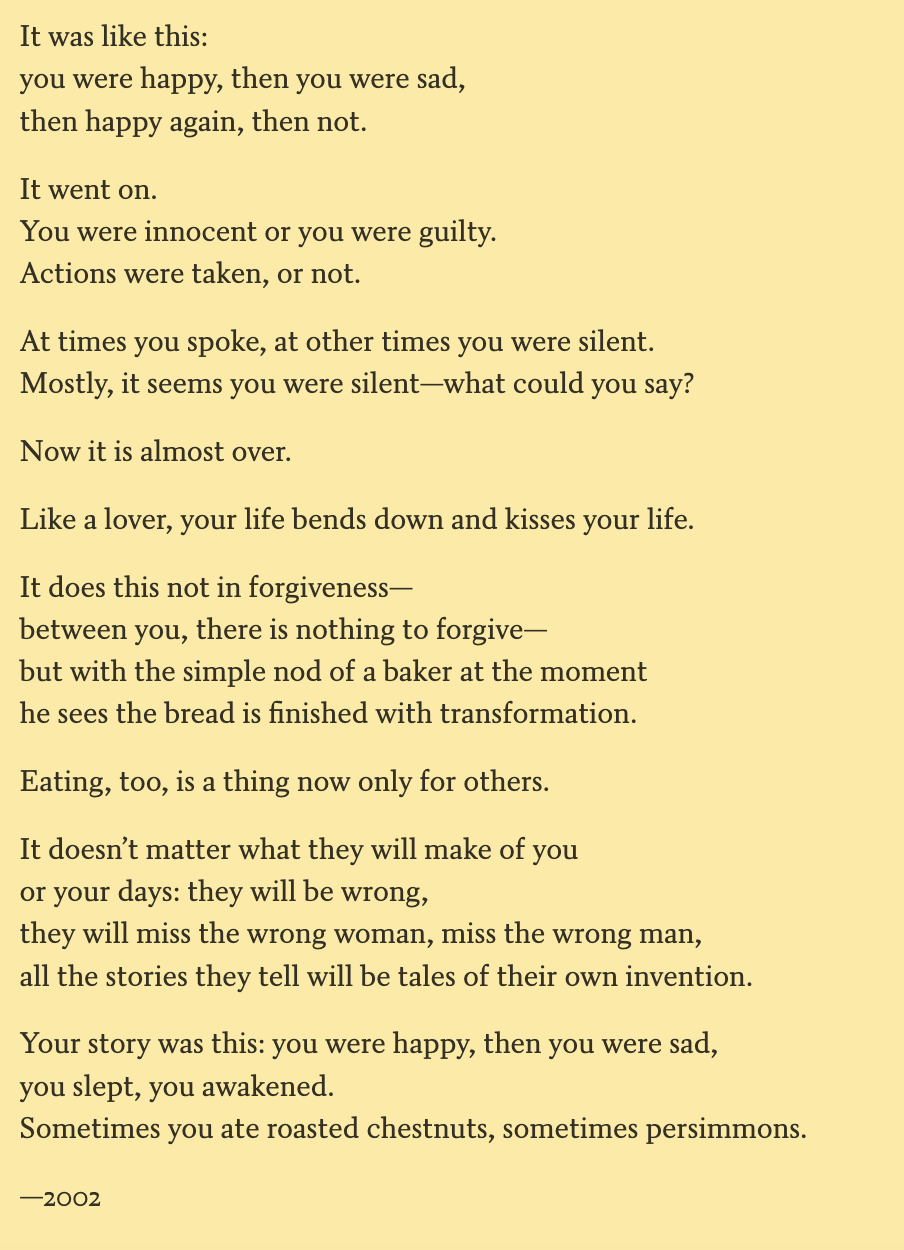

poetry pocket: it was like this: you were happy, jane hirshfield.

it doesn’t matter what they will make of your days: / they will be wrong, they will miss the wrong woman, miss the wrong man, / all the stories they tell will be tales of their own invention.

“You may do this, I tell you, it is permitted. / Begin again the story of your life.”

–Jane Hirshfield, “De Capo”

dear little voice,

this week: you are happy. this week: you are sad.

perhaps with roasted chesnuts, perhaps with persimmons.

for Hirshfield, every poem begins in a Language awake to its own connections:

“…language that hears itself and what is around it, sees itself and what is around it, looks back at those who look into its gaze and knows more perhaps even than we do about who and what we are. It begins, that is, in the body and mind of concentration.

By concentration, I mean a particular state of awareness: penetrating, unified, and focused, yet also permeable and open. This quality of consciousness, though not easily put into words, is instantly recognizable, Aldous Huxley described it as the moment the doors of perception open; James Joyce called it epiphany. The experience of concentration may be quietly physical--a simple, unexpected sense of deep accord between yourself and everything it may come as the harvest of long looking and leave us, as it did Wordsworth, amid thought ‘too deep for tears.’ Within action, it is felt as a grace state: time slows and extends, and a person’s every movement and decision seem to partake of perfection. Concentration can be also placed into things--it radiates undimmed from Vermeer’s paintings, from the small marble figure of a lyre player from prehistoric Greece, from a Chinese three-footed bowl--and into musical notes, words, ideas. In the wholeheartedness of concentration, world and self begin to cohere. With that state comes an enlarging: of what may be known, what may be felt, what may be done.”

Jane Hirshfield, from “Poetry and the Mind of Concentration,” Nine Gates: Entering the Mind of Poetry.

and magnetism:

“The poems we remember hold in themselves something startling and unexpected, some undertow, some magnetic pull toward a fuller, subtler truth.”

Jane Hirshfield, The Promise.

much of Hirshfield’s own Zen practice dances with the small-sized miracles of things; with the impulse toward limpid astonishment lying dormant in the otherwise everyday, and transformed in the heart of the Artist:

“Poems appear, as often as not, to arise in looking outward: the poet turns toward the things of the world, sees its kingfishers and falcons, hears the bells of churches and sheep, and these outer phenomena seem to give off meaning almost as if a radiant heat. But the heat is in us, of course, not in things. During writing, in the moment when the idea arrives, the eyes of ordinary seeing close down and the poem rushes forward into the world on some mysterious inner impulsion that underlies seeing, hearing, and words as they exist in ordinary usage.”

—Jane Hirshfield, from “Kingfishers Catching Fire: Looking with Poetry’s Eyes,” from Ten Windows: How Great Poems Transform the World (Alfred A. Knopf, 2015)

Jane Hirshfield, Autumn Quince.

you can listen to Hirshfield speak of the transcendental everyday in this wonderful interview with Mitzi Rapkin here:

“…if I had a better memory, I could quote, there’s some famous line of poetry about how the tiger’s claw makes the gazelle as lithe and shapely and fast as it is. Evolution created both. What we find beautiful, I think, is very often what holds the value of life. The most quotidian thing does. You can get lost looking at a bowl if you open your eyes thoroughly enough. There is nothing ordinary that doesn’t have the capacity for extraordinariness in it, and I think that’s a great deal of why people write, why we write, why we make art, or why we paint because the very activity of turning in the direction of art is turning in the direction of seeing with more saturation, fullness, amazement, simply the saturated existence that’s always here, if we can only manage to see it and find it.”

or read more of her electric relationship with language in this brief interview here:

“Poetry itself is a paradoxical intertwining of intimacy and distance. What begins in the body, in the life, in the heart/mind, leaves that interior existence when it sets forth into language. Yet the language of poetry and art is an attempt to awaken inside the body and life of another what was yours. Our tongue, our pulse, our breath, our heart, our mind, are inhabiting the gestures and patterns the poet’s tongue, pulse, breath, heart, mind placed there. To say, or read, your own poem, is to return yourself to a condition that stepped into being in its making. Poems implode time and space, in their ability to summon and resummon a particular shape and constellation of presence. They are perfume bottles momentarily unstoppered–what they release is volatile and will vanish, and yet it can be released again.”

Jane Hirshfield, from “Open Secrets: An Interview with Jane Hirshfield,” Passwords Primeval: 20 American Poets in Their Own Words, ed. Tony Leuzzi (BOA Editions, 2012)

love,

ars poetica.

So few grains of happiness measured against all the dark and still the scales balance. The world asks of us only the strength we have and we give it. Then it asks more, and we give it.

- Jane Hirshfield, from “The Weighing,” in The October Palace

I miss the wrong woman almost everyday. my tale is mythic and awakened by fear. i used to practice Zen studies with tai chi. i learned about eastern philosophies during my existential phase. i felt very alone although i was surrounded by light beings. i experienced relationships that would transform my personal wanderings. i would feel the pain and loss and angst as if the people died inside me. i resort towards poetry for a way to exhale my ideas.

"Poetry itself is a paradoxical intertwining of intimacy and distance." This to me is one of the great things about it, the frisson, the liminal, going from edge to edge. Too much of one or the other is not poetry, or not what makes it exciting and great, therapy on the one side, intellectualizing on the other, ie. no tension. I'm guilty of both.