what do we do when we are dying?

because you too are not so unlike these trees. it would be easy to say that this is because you are alive— but no, it is because you are also dying.

dear little voice,

in memory my most beautiful days exist always in autumn— no matter the moment, no matter the season.

in autumn there are twelve hours of light on each day, and everything rings out of itself most clearly as if struck like a bell— the green fading and then flaming into May’s loveliness: vermilion sumacs and scarlet maples, lemon-yellow poplars and golden hickories. autumn comes with quiet feet and covers me with this haze, like a white sheet that has blown all day in the sun, like a mountain lake shaken with a body, it slips over me— it is the way that autumn air seems to accumulate around my body in a deep, dreamy silence, soft and dense like powder, that has me look at everything closely— even the things that cannot be looked at, things like the air, like the breath that comes off of trees, the scent of winter flowers through open windows, the sounds of it all: of the wild, the wind, the wetness in the falling leaves, autumn, bitter smell of foliage, scattered pieces of an elm tree— I take corners like these ones, small pieces of my naked pleasure left lying around that can be collected and stored; there will come another season i will need to know i was here.

people never even notice i carry these with me always, they are so light and so easy to hide.

Guillaume Apollinaire, tr. by Anne Hyde Greet, from Calligrammes: "Song of the Horizon in Champagne”

artists, writers and painters have long been concerned with the seasons, and with autumn in particular. George Eliot wrote: ‘Is not this a true autumn day? Just the still melancholy that I love – that makes life and nature harmonise’. Rainer Marie Rilke observed, ‘at no other time does the earth let itself be inhaled by one smell.’

it is autumn also that Edward Hirsch calls upon in his poem Fall to denote that brief and startling moment, walking alone, that we realise just how much we have changed— and how there will be another moment, another street, another evening, another striking recognition in the future when we realise that we have changed yet again. and another. and another:

“Around us even as its colorful weather moves us,

Even as it pulls us into its dusty, twilit pockets.

And every year there is a brief, startling moment

When we pause in the middle of a long walk home and

Suddenly feel something invisible and weightless

Touching our shoulders, sweeping down from the air:

It is the autumn wind pressing against our bodies;

It is the changing light of fall falling on us.”

- Edward Hirsch, Fall. (excerpt)

Visitors pose for photos in the middle of the Lake Elsinore poppy fields in Walker Canyon, Autumn, Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times.

how much of this season is alive? certainly not much of it.

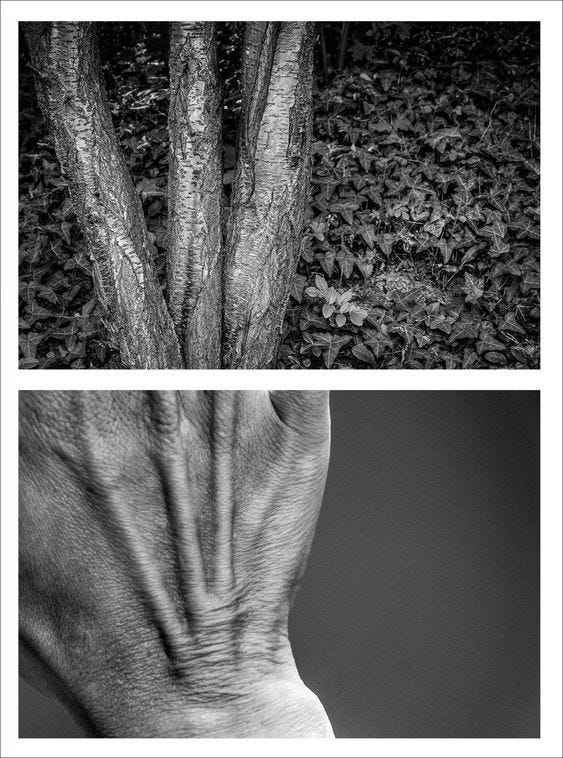

the trees now are blissfully imploding paradoxes alive in the yellow of autumn, the red of flowers, of flame— but their most outer bark does not live. instead, it peels away in arid, flaking sheets, revealing beneath it layers pallid and untouched. neither is their wood: a mere cicatrix of dead material clinging to the inner bark. if any part of the tree is alive, it is certainly not the parts of it that are immediately visible.

but still these trees flourish unfettered at the skin— sprouting the timid explosions of blossoms, supple twigs and sudden leaves— humble documentations of some persisting, inner aliveness.

this unseen aliveness is the tree’s cambium— the layer of cells scarcely a quarter-inch thick that acts as a slender intermediary between its bark and its wood. on one side, this layer succumbs to the stasis of wood; on the other, the dead bark. but this living stratum— this delicate boundary between the nascent wood and bark— although unseen and unknown, is a pulse persisting so that the tree might still bloom.

you too are not so unlike these trees. it would be easy to say that this is because you are alive— but no, it is because you are also dying.

as Edwin Tenney Brewster writes in Natural Wonders:

“Our hair and nails are not alive at all, and that our outer skin, the thin skin, that is, which we tear off when we bark our shins, is fully alive only on the inside. Our “bark” in fact, is very like a tree’s. Each has a soft, thin, living layer on the inside, which grows, hardens, dies, forms a water-tight layer over the rest of the body, cracks into scales, and drops off. Where one forms cork, the other forms horns.

The blood itself is dead. The watery part is just soup; water and salt and fat and jelly. The minute, coin-like, red blood corpuscles carry the oxygen of the air from the lungs all over the body. But there are similar oxygen-carriers, likewise dead, in bottles in the drug-stores. The corpuscles are dead cells alive once, and like the hard skin cells, a great deal more useful dead than alive.”

- Natural Wonders, Edwin Tenney Brewster

it is true that the largest, oldest trees possess a greater quantity of dead wood and bark in comparison with more modest shrubs, herbs, and grasses. and these smaller plants, in turn, contain more living material than the simplest of organisms—the little aquatic plants, yeasts, and moulds—that thrive without the weight of any dead material at all, let alone wood or bark.

as Brewster writes, this paradox extends to the animal kingdom. creatures as ethereal as jellyfish and as minute as infusoria, devoid of skin, hair, bones, nails, or blood, are almost totally unburdened by any dead structures.

and so an inverse relationship begins to reveal itself: the greater and more expansive the life, the more that the structures that support its aliveness are, paradoxically, dead.

i love autumn because i love borders and the places between things.

as a season it is a sort cambium in this way; a delicate territory of exchange between what is living and what is dying in the earth. like the trees it shakes leaves from, it is kept alive in its dying, delicately forming the very dead structures that flowers will emerge from, tangled and wild, in the coming seasons. and the more the tree releases, the stronger the future architecture of its aliveness will become.

may is one of these borders between summer and autumn and for this reason it is the most beautiful place i know. twilight is the border between day and night, and the shore is the border between sea and land. all of these places are places of revelation that to the untrained eye appear to be places of loss— the sea pushes itself upon the land and draws back to reveal shells like the scattered petals of white roses, brilliant reflections, clusters of collected husks, hulls, shells, scavenged boats of milkweed pods, rattlesnake grass and clover; at evening the Sun isn’t overtaken by darkness but parts to reveal the Moon: ancient, flushing, as white and as naked as a plate.

to likewise say that autumn is simply a season of decay would be easy— it serves also as a season of revelation. across centuries, stories, and lazy chatter we have believed the hot-gold hues of autumn leaves to be evidence of death and decay, and springtime’s flush of green to be a symptom— boundless, giggling— of life. this colour is the product of chlorophyl— from the Greek chloros, meaning color, and φυλλον, meaning leaf— the chemical that provides trees with the delicate mechanics by which they capture and convert light into the sugars that create that familiar green hue.

but as we drift into autumn and the air cools and sun slows, trees begin to cease their chlorophyll production in preparation for winter: a necessary retreat from the taxing endeavour of growth. it is this ease that allows the tree’s natural pigments, so far hidden throughout the year—xanthophylls, carotenoids, and anthocyanins, to name a few—to surface unconcealed.

in other words, autumn’s colours are less a symptom of a fading, and moreso one of an intense enflaming— not of decay, but of deliberate unfurling. it is no wonder then that it shares its colours with the phoenix from our childhood stories: a potent symbol not only of the loss of resurrection, but of what it later reveals.

becoming is like autumn in this way: like poppies and leaves and revelation— a bright red flash, fresh, blowing about. yes, the seedheads will need to rattle, and the seeds fall out, and the leaves from branches also. but autumn fades, winter leaves— and then suddenly, from the cambium, there is a thrum, persistent— a pulse from which more is waiting to spring up and flower, made stronger and more honest from the architecture of what it has lost.

i was walking this morning through the brilliant autumn maples and thinking that there is something so lazy and so lovely about how in this season the earth rolls over and simply suns herself in rest; she lets go and falls and falls and falls: leaves from branches, swallows’ wings toward the earth, the blind, neutral dripping of the trees, even the way the flowers bend backwards. these are slight, intimate hours where the earth is made all strange again; strange like nakedness and like fairytales; like glances and faces from a gone-now past. sitting beneath the red ficus i realise that all of this light is just loss explaining itself through a series of colours—hectic orange, flagrant red, a kind of gold that speaks directly to god or moonbeams or silence— and i think: perfect, naked autumn: i love you for this. all my memories create themselves again for you.

quietly, i take this corner: this small piece of my delight left lying about that can be collected and stored.

there will come another season i will need to know i was here.

to be at a border is to say goodbye.

this is something human beings exert vast portions of our energy devising antidotes to. this is strange when one considers that most of the bodies we live in are dead, dying, or gone, and that it is these dead structures that allow us to be brighter, more brilliant, more expansive— how in a universe where leaves fall and fade, governed by relentless change, we hunger for the the familiar comforts of stasis and pattern.

but to be at a border is also to be on the way. and to be on the way is a most important thing to be. being on the way is like this: like vermillion, sumac, goldenrod, like chicory and chestnut flower— an unhesitating autumn of colours flaming a thousandfold into light.

if you are quiet enough in autumn you will notice that it is speaking to you like late rain, like what clings to leaves, like what shakes with a light wind. in the grassy moonlight it says: you are aster and you are pearl, you are viburnum, trillium and white star, you are meadow and sky, the bitter earth and all the sugars of flowering, soil-sweet and undone— you fall from the sky in uncertain flowers, you spill, you come off of yourself in waves, your home is nowhere, you are always changing. therefore you are your own dwelling, your own kind of welcome, own kind of song, free of any kind of knowing you can put a name too, but closer than anything to it for this. you too are a border; you too are this place of absolute unformed beginning.

like most beautiful things rarely do we pay autumn enough attention. when i look at autumn i see the season for borders, for becomings, and for goodbyes— but also for crossing over, for revelation, and— most wonderfully— for colour.

the morning before the poet William Stafford died, he drafted a poem containing these lines:

“You can’t tell when strange things with meaning

will happen. I’m [still] here writing it down

just the way it was. “You don’t have to

prove anything,” my mother said. “Just be ready

for what God sends.” I listened and put my hand

out in the sun again. It was all easy.”

the question Stafford is asking in this poem is the one we have been asking since we began this letter: what do we do when we are dying? and on a more intimate scale: what do we do when we are saying goodbye— goodbye to love, to ideas, to certainties, to one future, to another?

we do as the trees do: we read literature. we remain present. we make love. make coffee. write poems. read the newspaper. cry. stew apples. take our shoes off beneath the table after a long day. call our friends. walk among the maples. listen to music on the floor. pick flowers. make the bed. take pictures of the Moon. fail at it. think about what that means. search for clover. wonder. run a bath.

you look at the falling leaves long enough, with no thoughts in your head, and you gradually feel your body shaking loose, coming free. you have nothing now but what was always there, and what is gone but still clings to you in death, in memory, only makes you larger, greater. and it happens that you cannot turn around or go back, but soon you will find yourself where you will be at the end, and you will tell yourself then, in that final floating, that you love all of what you are.

simply: we amuse ourselves, while we still have the time.

love,

ars poetica.

little voice: it is my belief that Poetry is a human birthright. it is for this reason that my work will always be completely free, but it takes considerable Time and Love to give to you each week. if it has brought you something, please consider buying me a book so that I may continue to tuck Words in your pocket:

Ah, if I must choose, then winter is closest to my heart. And Autumn is the prelude to winter . As with each season, I can speak of endless joy from the archives of my memory. So many beautiful passages you’ve given us. Especially the last few .If you don’t mind I have taken bits and pieces of your beauty , solely to answer this question. ( I would never have done this if it were a poem)“What do we do when we are dying”

Just for myself , to remember at the very end. So someday when it comes my time I will hope with all my heart and joyful memories, this is how I’ll go~ “…it is the way that autumn air seems to accumulate around my body in a deep, dreamy silence, soft and dense like powder,” And I’ll remember this

too ~“ …that all of this light is just loss explaining itself through a series of colours”

And I’ll take with me ~“…colours flaming a thousandfold into light”

Thank you for that.

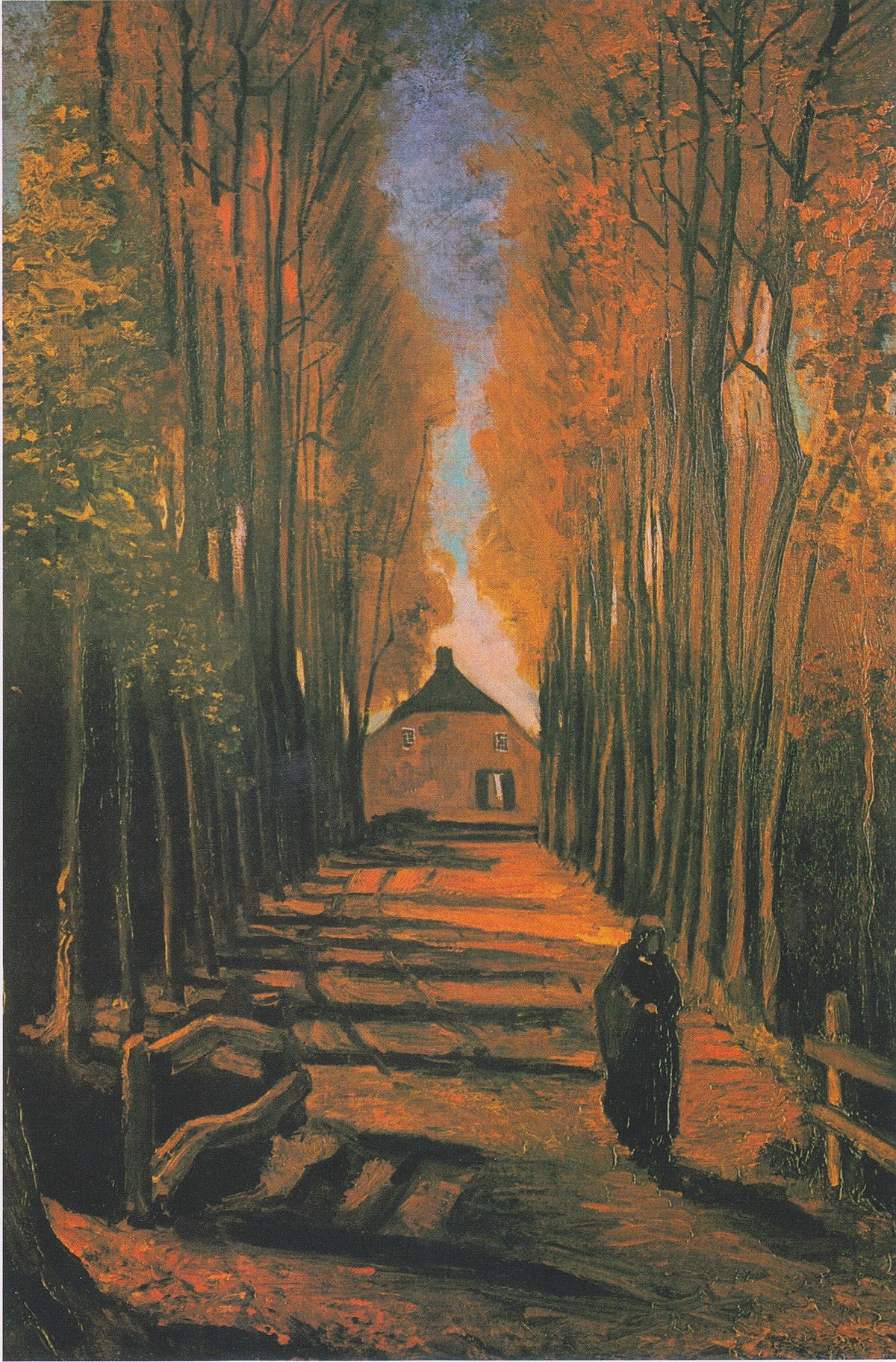

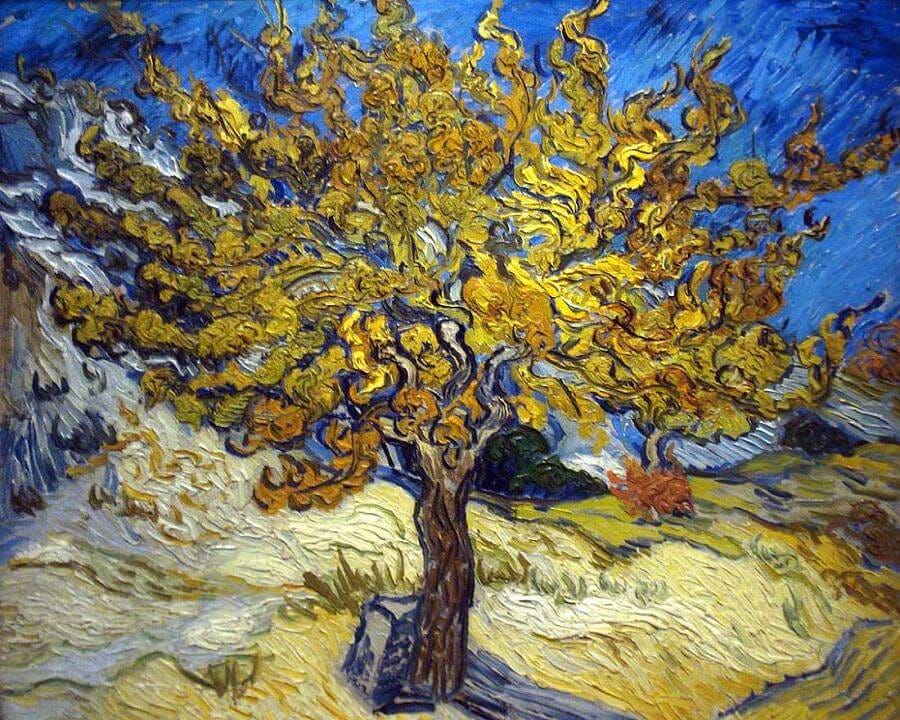

Van Gogh , what a glorious tree. I have never seen this particular painting before. Obviously he knew trees and felt the spirit of this one dancing free in the wind and reaching to the heavens .I sincerely thank you for all . And for introducing me to The Mulberry Tree in Autumn.

much of this lingers on the edge of things i’ve been considering myself lately… this was lovely and comforting to read