to be alone is not an option, and other rules for becoming moss.

now, a word of caution: when you first decide to become moss, there will be many people who try to convince you otherwise.

dear little voice,

when you first decide to become moss, there will be many people who try to convince you otherwise. this is, upon initial inspection, a reasonable request.

Spanish Moss on a Humid Morning in the Swampland, Doug Hicock

they will first try to do this by making a great fuss over the fact that you are, as of this moment, indeed not moss.

they will fill the magazines with it. they will call you to tell you on the telephone. they will make great displays, tug at your sleeve, and maybe, if you are particularly good at not being moss, occasionally give you a certificate for it.

they have even given Not Being Moss a name. they call it: having a myself.

the popular magazines are filled with all kinds of advice on things to do with this myself: instructions on how to find it, on how to make it better, make it stronger, make it more attractive and, occasionally, lose it for a moment. they call this last thing having fun.

we like to make this myself the best myself it can be. some of the myselfs that have become particularly adept at being a myself have written many books on the subject that are equally as thorough as they are confusing. sometimes myselfs climb mountains or sit down with their eyes closed for a long time or travel to distant places to sit in rooms with styrofoam cups and clap as one myself stands on a large stage and teaches the other myselfs all about having a myself and developing a myself so that it is an even bigger and better myself. having a myself is even taught in schools. many take lots of pictures of their myself and try to make it look like the best myself they can. some even make a career out of it.

you would think, little voice, that we had only just discovered this myself; that we had for a long time suspected in secret that there was something alive with heat and legs running about inside of us, utterly a-glow and precious and seperate from the rest of the world— and, at last, now that we have been given permission to play with it, it seems to be very much all we can think of.

so, little voice, we do not think very fondly of being moss. we would rather be a myself. after all, to a myself, a moss is a flat and green and unspectacular thing. myselfs do not have the talents of a fly’s extraordinary panoramic vision. nor do we have the acuity of an eagle. and so our time in our brief and big brains in spent, most usually, considering myself.

the moss beneath us, rosy with a perpetual bud, parting curl upon curl and softening into its acres, appears to us to be only a flat projection of some green thing without a myself; mere wrinkles in the earth condemned to suffer what is the strangely inexperiencable but altogether tragic tyranny of lacking consciousness.

but we are perhaps equally oblivious in our passage overhead. important stories and lessons are blossoming beneath us that we do not see. our vision at this grand scale is in this way impractical; perhaps not because of a failure of our eyes, but because of a failure of our egos.

but: if you are still reading this, little voice, you must be curious. this is of course the correct condition to be in under most circumstances.

and so, quietly, i will show you how to become moss.

1. understand that to be alone is not an option.

the quietness of moss and lichen gently conceals the complexity of their inner lives.

this is because to be moss is to be nothing less than a breathing rendition of life’s interconnectedness in miniature.

As David George Haskell writes in The Forest Unseen :A Year’s Watch in Nature:

“Lichens are amalgams of two creatures: a fungus and either an alga or a bacterium. The fungus spreads the strands of its body over the ground and provides a welcoming bed. The alga or bacterium nestles inside these strands and uses the sun’s energy to assemble sugar and other nutritious molecules. As in any marriage, both partners are changed by their union. The fungus body spreads out, turning itself into a structure similar to a tree leaf: a protective upper crust, a layer for the light-capturing algae, and tiny pores for breathing. The algal partner loses its cell wall, surrenders protection to the fungus, and gives up sexual activities in favor of faster but less genetically exciting self-cloning. Lichenous fungi can be grown in the lab without their partners, but these widows are malformed and sickly. Similarly, algae and bacteria from lichens can generally survive without their fungal partners, but only in a restricted range of habitats. By stripping off the bonds of individuality the lichens have produced a world-conquering union. They cover nearly ten percent of the land’s surface, especially in the treeless far north, where winter reigns for most of the year.”

for moss, “to be alone is not an option.”

moss does not resist the necessity of its interdependence: they are living, breathing symbiotes who create a sensual intimacy of this spectacular codependence, fusing their bodies and intertwining the membranes of their cells like ivy excitedly clambering a trunk.

if you are to be moss, survival will become simple, because it will depend upon simple, specific focuses: the way the sun passes through the hard sky to warm the Earth, or the way dull clouds part sideways for spring rain, or the measurable closeness of another body to yours.

inseparable from one another and without resistance to this generous and generative inter-existence, it is perhaps for this reason that moss are so very capable of covering so much ground.

2. forget myself.

little voice, words can be thought of as equal to the buds of flowers, in that we often mistake them for the whole sum of themselves.

just as a flower is only a flag to the delicate myriad of intertwined seedlings and roots beneath its soil, words too are merely the children of a thousand endless collisions in the history of language and human exchange.

in this way, words are not static things: they insist on evolving with us.

they, too, carry our histories. and just as history often does, when we have lost our way, they can gesture toward our roots in order to remind us of our most tried and true path toward the Sun.

take, for example, the word myself.

tracing our fingers along its flowers, we can find the root of the word self in the Old Catalan se or seu. in our human history, these are not words that referred to a myself but rather an otherself. you see little voice, seu was a pronoun used to refer an other person. indeed, most of the child-words of seu were created in order to refer to other selves somehow connected to our own. it is for this reason that the word has also been used to create words outside of or apart from the myself. this is where we take words such as secret and seperate. .

from its root, seu grew buds— swedh, or ‘others’— which blossomed into the Greek word ethnos. this is where we pluck words such as ethnicity and ethnography. in its essence, little voice, at its very core, the word self is asking you a profound question. and this question regards how you inhabit the world with others.

to be a myself is to feel at your ankles the persistent swell of an undercurrent of questions:

‘who do I want to be?’ ‘who am i?’ ‘how can I be happy?’

these are questions as ancient as they are urgent.

but to be moss, little voice, means to replace these questions— even for a moment— with: ‘what kind of World do I want to inhabit with others?’

to be moss is to understand that there is no division between the myself and the otherself. it is to understand that they share histories and lives.

it is to know that the drama and scale of survival begins in the most quiet and misunderstood of ways— moving closer to one another:

“The fungus body spreads out, turning itself into a structure similar to a tree leaf: a protective upper crust, a layer for the light-capturing algae, and tiny pores for breathing. The algal partner loses its cell wall [and] surrenders protection to the fungus.”

of course, the only sane response from either organism is, in the instance of this gesture, to glitter:

3. to re-shape the earth, simple reach outwards.

if you are to become moss, naturally you are going to clamber the earth’s surface in a glorious rigmarole of green.

when you do this, you will be reminded each day that the vital force of life is not one of competition, but one of generative interdependence.

lichen is a lovely, lucky thing. it coats the earth. and in order to begin its giggling ascent, moss takes the hand of the other beside it, nourishes it, feeds it, dampens its earth, shatters itself into a thousand pores for breathing, a thousand refracting chrysalises of light with which its lights the way for its fungal friends, and insists on growing together.

if you do not need to live for yourself only, if you for a moment have nothing to prove, if the ruckus and rolic of sheer public opinion quietens, if you side-step the snare of ambition and you are left in the swift and delicate silence of being moss, you are able, little voice, to ask yourself a very intimate question:

‘who do I want to be, here, for other people?’

beneath the anxious tremors of myselves, beneath their frigid fears, beneath their wavering convictions, this mossy pilgrimage is what they long for: a tenderness that begins with the simple drama of extending outwards, connecting with what is beside them, and translating it into light.

the most radical thing moss can do is to care for other moss. this is something that myselves have been taught is a moral fable reserved for children’s storybooks and hallway conversations.

but it is true, little voice, that tenderness is a profoundly radical response to a world in which it continues to waver.

to commit to the invisible nursing, nourishing, and caring for other— to extend beyond oneself and simply give— is to take profoundly seriously the very real fragility and pain of the little voices that surround us. there is not a person in this world who has not had their heart broken. moss honours that, supports that, empowers that, and connects with it in order to create light.

this is the practice of community and protection: a radical togetherness, an interdependent care, a politics of love.

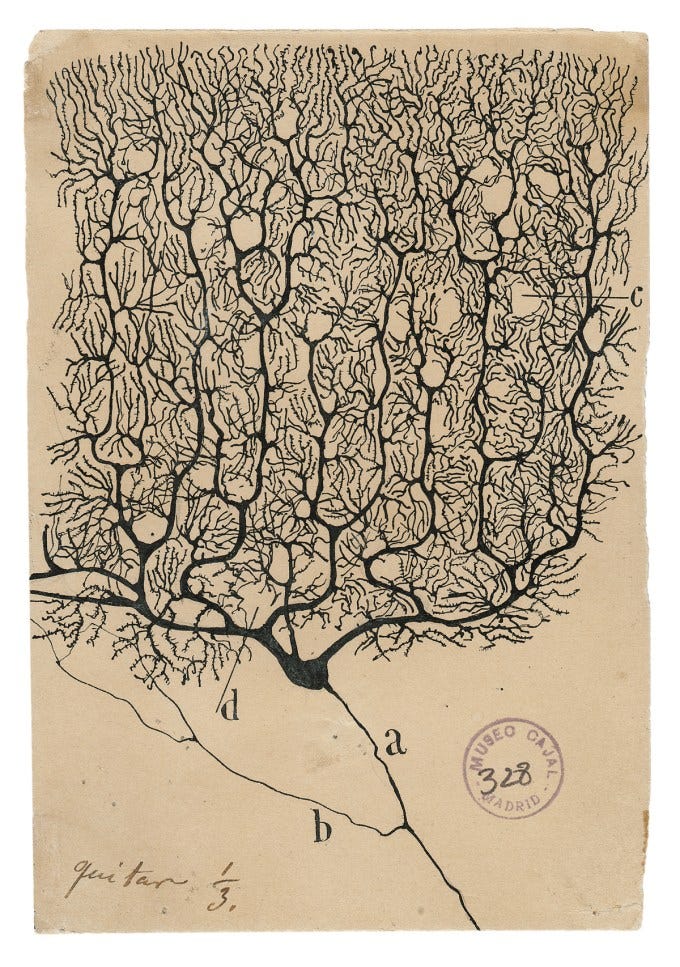

Neurologist Santiago Ramón y Cajal’s sketches of a purkinje neuron from the human cerebellum

4. insist on a naked Heart.

real bravery is often invisible.

for moss, bravery means turning over and baring soft, delicate bellies— prime snacking for hungry birds and other ruthless predators— regardless of fear. this is where they wait— sometimes for hours, sometimes for days; vulnerable, baring themselves utterly freely— until another algaic friend, extending outwards, delicately begins to coat them with tiny pores for breathing and delicate cells for shattering the air into colour and light.

but this friend must also shed their belly, and bare themselves freely, if they are, together, to begin to re-shape the earth.

invisible bravery means opening up, without resistance or embarrassment, and taking one another by the hand. it is the child of tenderness. it emerges in an invisible eruption when little voices let others brush against their hearts until they are simply raw with them. it is being willing to share oneself with others— in all of our precarious, divided bits, shrewd missing parts, incomplete shadows and misconfigured devices.

this is how we begin to re-shape the earth.

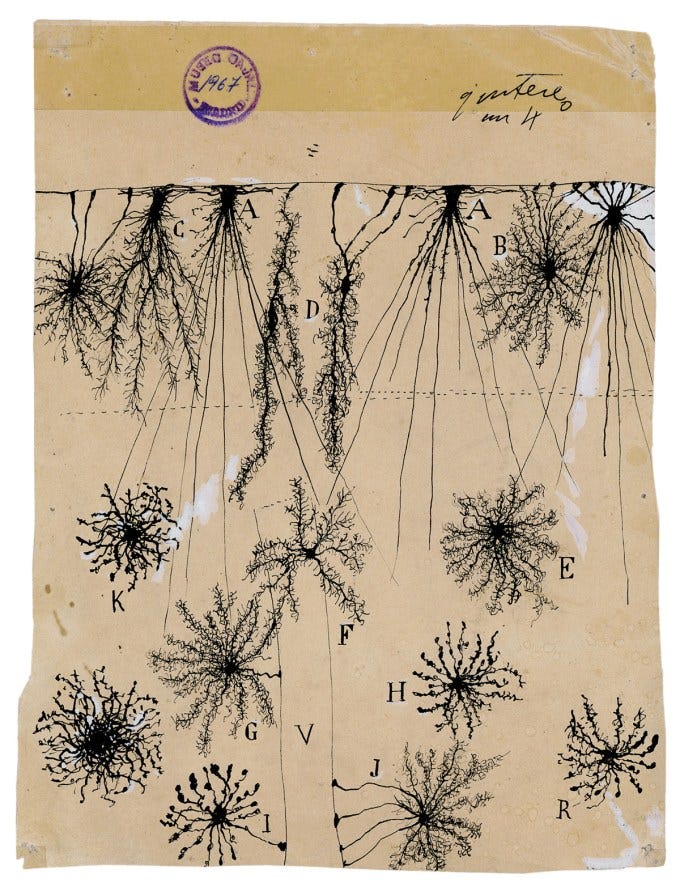

Santiago Ramón y Cajal’s sketch of the human brain’s cortex.

little voice: between birth and death, we wander our little earth-marble, the world around us only a complicated projection; a wrinkle in our experience of our myselves. oblivious in our passage, we forget the stories unfolding on either side of us: somewhere, a woman tucks a flower in her pocket, a grown man decides to pursue ice-skating, a child reads their first word, someone is being welcomed home, someone is being asked to leave, packs a suitcase, and stands in the doorway, separated lovers hear the same train pass through their cities, one after the other, and pause by their windows.

but so often the only story that does not escape us is our own.

“Coral, spread fingers, birch twigs, a loosely knotted fishing net, crystals, river deltas, ivy, mackerel clouds, women’s hair…diverse as these phenomena are and formed from opposing elements, nevertheless they all revolve around the invisible joints, their opposite forms touch even though they are far apart…and if I imitate their form, reaching my arms to the sky—moving them together and apart in turn, waving them to and fro—then [I am] no longer alone…I am the brother of all that divides, all that curls, all that intertwines, all that waves…”

and so— to answer your query, little voice, i have heard that it is easy.

there are, after all, only four rules.

love,

ars poetica.

little voice: it is my belief that Poetry is a human birthright. my work will always be completely free, and takes considerable Time and Love to give to you several days a week. if it has brought you Joy, consider buying me a book so that I may continue to tuck Words in your pocket.

Little voices

Moss are Earth's stewards of prosperity and self-growth. I read the entire chapter on how Nature shapes ourselves and instructs us to value its offspring. We often neglect what we are born into. Lichen expand their territory as we learn more about my selves. It's not to be taken with triviality. I think there's beauty underneath things in their shadowlands. Thank you for this reminder. Go forth and multiply.

gorgeous.....

and opens the my selves of myself

now considering their pieces and ways

thank you