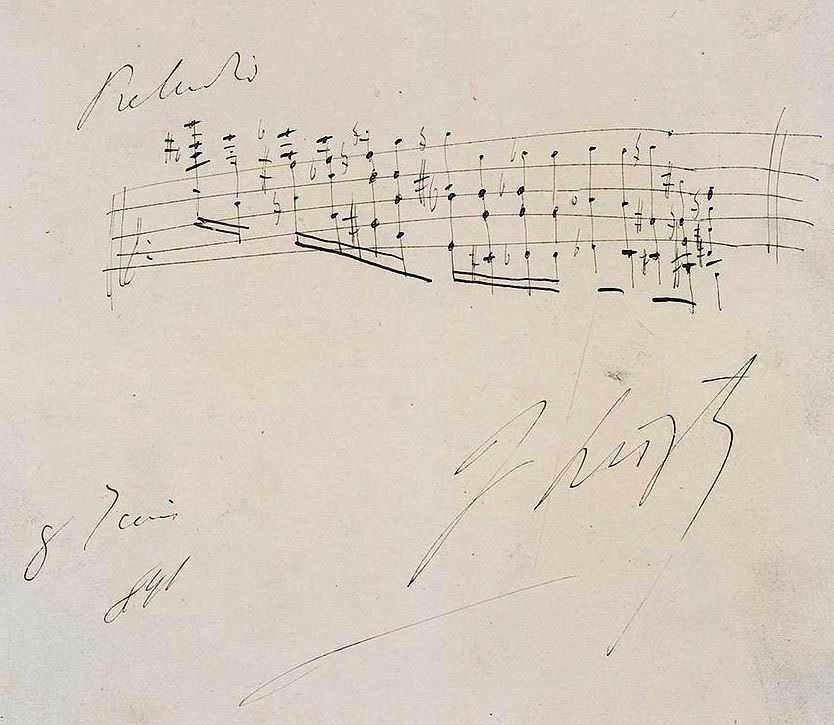

what you are hearing in this moment is music

when someone speaks to us, it is much more than a casual creation of sound.

a brief note: little voices, some of you have requested to walk with me and listen to our letters. if you would like, you can choose to pocket my voice and listen to this letter below:

dear little voice,

when was the last time you were listened to?

truly listened to.

listened to with the patience of a shell held to the ear. with the silence of leaping tides and of quiet trees and of the hush of stones; as though your words have the earth inside them for parting with palms and digging.

this kind of listening creates a kind of being heard with the whole body. and these kind of listeners are rare— but they spill a kind of unforgettable radiance you ache to be close to as soon as it is gone.

quiet your eyes and still yourself now— you will remember when you were once heard this way.

it is the kind of listening that can look into the most hard-strung swervings of a riddled heart and tug from it a place with the gentle presence of stars: a place immediately diffuse, warm, and safe. it is the kind of listening that when you consider that it does and will and might happen to be near you again— for a moment you feel less like a little voice, and more as though you may, in fact, be music.

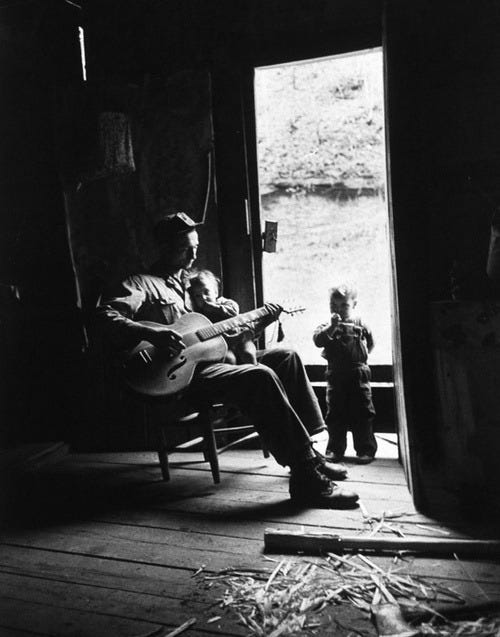

little voice: when someone speaks to us, it is more than a casual creation of sound. it is a request for permission: permission to be heard. and the great responsibility of having this permission sought from us is one of the simple debts we owe to being present in the miracle of the world at all: to look after one another, while we still have time.

as a species, we tend to think of intimacy as closeness, and of closeness as touch. what, then, could be more intimate than the breath that floods your body at once departing it and meeting in the centre of yours and another’s, only to be drawn in by the listener in an atomic exchange of the very air that draws the blood to your cheeks, the beat to your chest, and the Poems to your Heart?

for another little voice to speak their story into existence, and for you to listen, is to draw the voice of their inner life into the world: or, in other words, to permit it an existence in reality.

this is perhaps why the psychoanalyst Erich Fromm wrote that listening is an art like the understanding of poetry—

and this is perhaps why Kafka wrote that the task of poetry is to lead the isolated human being into the infinite life.

e.e. cummings, from “i spoke to thee” (from Tulips), Complete Poems of E.E. Cummings: 1904-1962

sometimes a voice does not want to be a voice any longer. it wants to be something hard, and deep, and true: no longer abstract and alone, but rather something with discernible edges, both clear and seeable, open and accessible to another. it wants to be touched, and known. to be led into the infinite life, and to be told that it too is real, proving that the speaker does and will continue to exist away from the confines of their own body.

and so the voice harkens to breath, and beats back and forth between itself and the body that hears it, or even farther, hitching to the wind, drawn in the effortless clumsy flight of a bird or butterfly to the ear that welcomes it— for a moment recognising itself in the bravery of this beautiful, troubled dance: this infinite longing to be heard.

sometimes a voice does not want to be a voice any longer. it wants to take the path of music: to say what it will, and remain beautiful and attended to without clauses or terms— no matter the revelation. no matter the cost.

where you listen generously, you agree unconditionally to the importance of this. you become, little voice, an audience to another life, regardless of the tears that choke it or fears that snap at its heels— just as ears give a song the permission to exist beyond a voice.

and so it goes: a conversation becomes more powerful than any charged crystal, incantation, or sacred brook: a most powerful mutual act with the strength and gentleness to rehumanise and reinvent a voice as a song. a human as a bird— something alive, singing, and in flight between where it is born and where it is going.

the speaker requires the listener. and the listener requires the speaker. it is, in this way, a most intimate photosynthesis, with language passed between two bodies with the ease of air from trees to lungs.

there is a moment in Anne Carson’s wonderful collection of essays Plainwater where she writes:

“I have heard that anthropologists prize those moments when a word or bit of language opens like a keyhole into another person, and a whole alien world roars past in some unassigned phrase."

- Anne Carson, Plainwater

i have spoken with many human beings, little voice. i have listened, and i have failed to. i have been heard and i have not been heard. and i have learned that there is a large difference between speaking and being heard. between listening and hearing.

one is rigid, and the other is fluid. one is dead, and the other alive. one is flat, and the other is endless.

it is, somewhat, the difference between a closed and opened door: it is difficult to discern the importance of their differences until you attempt— as the speaker does— to approach it.

but it is about more than simply being quiet when one person speaks— if this were not the case, then a little voice could feel as heard by a sleeping body as they would an awake one.

the sheer radiance of being truly listened to with generosity and love cannot be approached by any air or shade, shale, quiver or lichen, wolf or rose, smile or infinite understanding in its power. there is nothing on this earth that can accept into it as much light as the attentive ear, whose presence spills like wine with all the informal bliss and presence of love.

quite simply: it creates that keyhole. it parts the secret centre within speaker and listener, and creates space for travel into what Kafka meant when he spoke to the infinite world.

and just as a keyhole requires both lock and key to create a true opening, listening demands that both a speaker and a listener leave a conversation fundamentally changed: they are now open.

there is a wonderful passage in Mary Reufle’s On Beginnings, where she writes:

“Some languages are so constructed—English among them—that we each only really speak one sentence in our lifetime. That sentence begins with your first words, toddling around the kitchen, and ends with your last words right before you step into the limousine, or in a nursing home, the night-duty attendant vaguely on hand. Or, if you are blessed, they are heard by someone who knows you and loves you and will be sorry to hear the sentence end. […] I have flipped through books, reading hundreds of opening and closing lines, across ages, across cultures, across aesthetic schools, and I have discovered that first lines are remarkably similar, even repeated, and that last lines are remarkably similar, even repeated. Of course in all cases they remain remarkably distinct, because the words belong to completely different poems. And I began to realise, reading these first and last lines, that there are not only the first and last lines of the lifelong sentence we each speak but also the first and last lines of the long piece of language delivered to us by others, by those we listen to. And in the best of all possible lives, that beginning and that end are the same: in poem after poem I encountered words that mark the first something made out of language that we hear as children repeated night after night, like a refrain: I love you. I am here with you. Don’t be afraid. Go to sleep now. And I encountered words that mark the last something made out of language that we hope to hear on earth: I love you. You are not alone. Don’t be afraid. Go to sleep now.

really, little voice, when we are spoken to, we are hearing the voice escape the body in the form of the same sentence strung up in different words.

most often, these words are some variation of:

this happened to me. i cherish this. it haunts me. i did this. i failed to do this. this is part of who i am. it will not dissapear. it will not depart me. it will not return. this does not escape me. now i am seeking its permission to depart me as a bird in flight. now i am honouring it by transforming it to words. now i am turning the good, dark work of my deepest cells: so calmly turning this voice to music. please tell me it is not imagined; that another voice can dance to it too.

Ella Fitzgerald singing at Mr. Kelly’s, Chicago, 1958, Yale Joel

when you are listened to with this radiance, you feel as though suddenly you do not need to know how many days line your life, or the hours until your final Poem. you need only find your way by following your own voice and the body that hears it; your listener, for a moment, indivisible from your own Self, because in this moment they are building you also.

this is a space in which we touch one another and create a new world. a world where stars move a different way. where both bodies end. where both begin. where we are heard. where we hear. where we both leave opened, and changed.

and this is why any utterance is magic, and why the space created by an open listener is even moreso. words have power— but less so for what they are, and moreso for the speaker’s trust in the listener to receive them. these conversations are alive, because they do things. they change things. these wild, strange sounds transform both the listener and the speaker permanently, their energy ricocheting back and forth as casually and carelessly as breath between trees and mouths.

Sonia Sanchez, ‘Haiku (for you)’, Like the Singing Coming Off the Drums: Poems

and this is why your listening has such power, little voice. it has the power to suggest all of this: to suggest that a voice is more than a voice; that it is also an alive and real entity. that its sound is more than words. that it is music.

listening is the task of easing the pain of living for others. it is not to be confused with the task of understanding, which would make it very difficult, if not impossible.

simply, listening is the task of being a mirror: of being a thing that reveals everything but itself.

in this way, true listening does not need to understand— because it is spared from calculation and critique. instead, it does not withhold, but pours itself in abundance without thought or hesitation, appearing for the speaker quietly in the every gap and crevice of their speech, not overhung nor hidden, both at hand and from afar.

this is why, little voice, the most generous listeners seem to compel words with the casual magic of the moon attracting water.

Kate Murphy, in her book You’re Not Listening, frames our modern lives as particularly antagonistic to good listening:

“[w]e are encouraged to listen to our hearts, listen to our inner voices, and listen to our guts, but rarely are we encouraged to listen carefully and with intent to other people.”

- Kate Murphy, You’re Not Listening

but it is a great privilege, little voice, to listen: to put yourself in the hands of music; of a real human being with humble raptures and real terrors and ascendencies, and commit yourself totally to the pleasures of this intimacy; of witnessing their fragile self-discovery through language. it is rich, and it is true, and— perhaps most importantly— it is maybe the only thing you are here at all to do at all.

A Bosnian soldier plays the piano in the destroyed music school, (1992) Teun Voeten.

That is what he did most of the time, when she was angry or sad or frightened: watched her and listened. He had told her he stopped believing in advice years before he met her, or stopped believing people wanted advice; they wanted to be looked at and heard by someone who loved them.

Andre Dubus, from “Out of the Snow”, Dancing After Hours: Stories

at the end of my life, when I say one final so, what have I done? i hope my answer is: i have given.

i know there is one way i can do that, and that is through listening, and through promising every voice i meet that it is music: a music that when i listen to, gardens open around me and the sounds become a flower heard with my body. this is to say: that their words become an invisible touch that finds its way through my lungs, and when it does inside of me it roars in perpetual Vivaldi, jasmine, sand, and endless topaz. and when it departs, it enters the speaker as an acknowledgment, and an oath: we are here, together, and i promise you, you are here, in the infinite world beyond yourself, and you are real.

Octavio Paz, ‘Letter of Testimony’, A Tree Within (trans. Eliot Weinberger)

so, little voice; i would like to leave you with something in your pocket for the next time another little voice makes an appearance by your own.

the beautiful psychoanalyst- and little voice in his own right- Erich Fromm, in his seminal work The Art of Listening, leaves us with six rules for coming into contact with another voice:

The basic rule for practicing this art is the complete concentration of the listener.

Nothing of importance must be on his mind, he must be optimally free from anxiety as well as from greed.

He must possess a freely-working imagination which is sufficiently concrete to be expressed in words.

He must be endowed with a capacity for empathy with another person and strong enough to feel the experience of the other as if it were his own.

The condition for such empathy is a crucial facet of the capacity for love. To understand another means to love him — not in the erotic sense but in the sense of reaching out to him and of overcoming the fear of losing oneself.

Understanding and loving are inseparable. If they are separate, it is a cerebral process and the door to essential understanding remains closed

you can listen with your eyes and your hands open, too. you can stand at this door to music listening, gasping, smitten and awed, like a child before god.

there are rare moments where these rules are chased and sought and followed— where words shatter and refract beyond unspeakability, and a little voice does not feel so little anymore.

i know i have thirsted for this like a violin waiting for the bow. how i have wanted to gather the feeling, to cup it like water in my hands and drink.

and what is a more natural and patient thing to do with what we long for then to give it as we wait for its arrival?

love,

ars poetica.

little voice: it is my belief that Poetry is a human birthright. my work will always be completely free, and takes considerable Time and Love to give to you several days a week. if it has brought you Joy, consider buying me a book so that I may continue to tuck Words in your pocket:

“I remind myself that language isn’t my job. Writing a poem isn’t my job. My job is the human job of waiting and listening, and language is just what poets use—like wind chimes—to catch the sound of the larger, more essential thing. Wind chimes themselves are not the point. The point is the wind.”

—Jenny George, in “Wilder Forms: Our Fourteenth Annual Look at Debut Poets” in the January/February issue of Poets & Writers Magazine (2019); read the rest at pw.org!

"where you listen generously, you agree unconditionally to the importance of this. you become, little voice, an audience to another life, regardless of the tears that choke it or fears that snap at its heels— just as ears give a song the permission to exist beyond a voice."

d e l i c i o u s

I don't know exactly where to begin or how to eloquently opine here. This particular article was beyond me. It was somewhere dense above the bold skies and below the deepened Universe. Listening is an Art form. Poets & other troubadours knew this instinctively. I suppose I once understood too. There is so much to this life that even me who tries to grasp these silent languages with an open soul. Music is everywhere. The dance of willow trees ruffling, the sound of a zen wind in the distance. We are super connected. Maybe I'm not as emotionally intelligent as I tried to express. I've been trying to touch the invisible audience in poetry. I've felt so many repeated moments that I failed to translate the metaphors. I do feel detachment welcomes change and self discovery. I've been denied so I have to apply new tools. Thank you little voices. This December has been about listening to things again. My heart needs to filled. Sensitive and intuitive.