keep no safe distance.

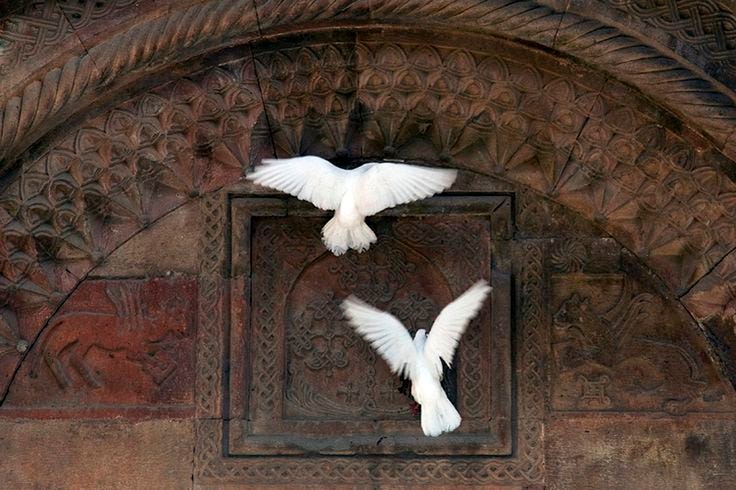

considering love, it is only natural that the mind wanders to the dreams of birds.

dear little voice,

considering love, it is only natural that the mind wanders to the dreams of birds.

Theodore Roethke, Straw for the Fire: From the Notebooks of Theodore Roethke

Amish Dave and Daniel Margoliash, biologists at the University of Chicago, have been looking into the restless machinery of zebra finch brains— the soft circuitry that makes birdsong possible.

finches, like all birds, are not born knowing their songs. no instinctual aria awaits them, perfectly formed, in the folds of their forebrains. instead, they must learn—note by note, breath by breath— in the part of their brains known as the robustus archistriatalis, where neurons fire after each note is sung. these subtle flares of electrical activity, precise and ephemeral— like light through a keyhole— are how Dave and Margoliash mapped the trajectory of their songs, hoping to reconstruct their arcs from start to finish.

but it’s at night, while the birds are asleep, that the story unsettles itself. the birds’ neurons don’t rest, but fire again and again— and not chaotically but with a sequence, as if their songs are being sung all over again, silently, while they sleep.

it is tempting to revert to the language of scientists and call this a neurological rehearsal; a kind of complex biological phenomenon necessary only in pursuit of survival. but instead i am sitting here considering love in the heart of december1. and i am thinking about how, in the haze of a defenceless sleep, the bodies of birds are not armoured against predators or catastrophe. totally vulnerable to the otherwise awake world, their neurons fire for no fretful rehearsal of escape routes or pleas for safety in the dark. instead: they sing.

that the body can turn away from its every instinct, disregard its every safety, and jeopardise its every chance at constance in order to simply make music strikes me as something worth remembering—that even a fragile body can abandon its learned caution and choose to sing.

the finches seem to say: there may never be safety, but there will still be music.

Jochen Lempert, Birkenzeisig (Redpoll Bird) from Vogel in der Hand, 1998

amor mundi was the word St Augustine gave to a love for the world. i am learning that this love can be fierce only if it is foolish. let me explain: i have wound my self preservation up in the fleeting; i have made sacred only what is untenable. i know this because my heart is its own hunter; i love only what is already dying: dusk and jetties and my own memory, slowly, the dried lavender kept in a knot beneath my pillow, the quiet embrace of stones, the way language folds around its edges in every name we’ve given to water—stream, creek, arroyo, tide— my grandmother’s hands, at once both familiar and made strange by time, holding the weight of years as if trying to balance time itself, lines from poems that arrive too late, the silhouette of my lover’s laugh etched to the air long after the close of the door. to put it otherwise: i love everything that does not know it loves me, or that doesn’t care, and so owes me nothing: no permanence, no stability, and certainly not any new arrival—just the uncomplicated and undiscriminating promise that it will leave me, too, very soon, and into what Mary Reufle called: “the end of time, which is also the end of Poetry (and wheat and evil and insects and love).”

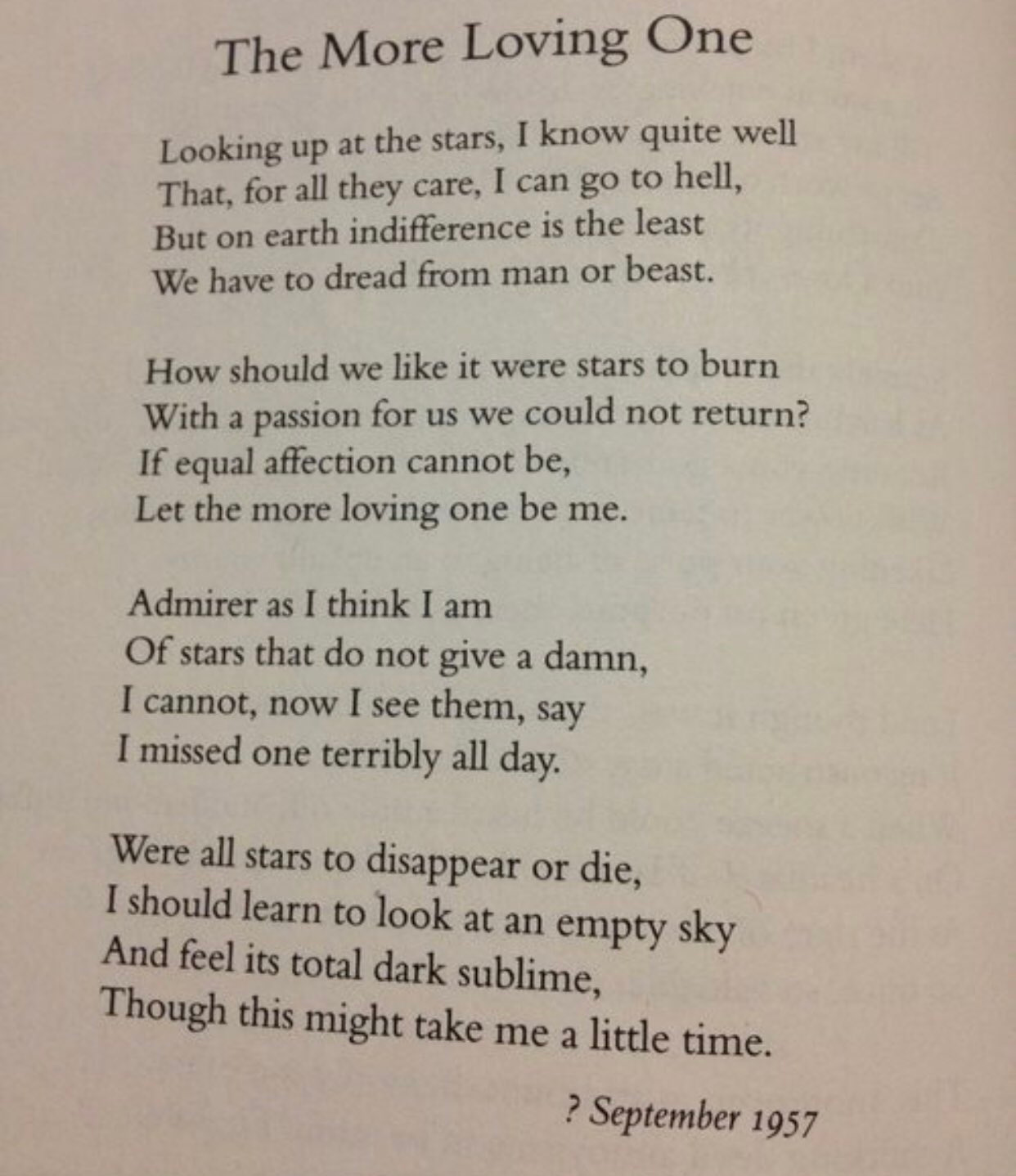

little do we last and the world is enormous. this is all that is promised to us. it’s perhaps why every time i fall in love, something throbs inside of me as light and as vulnerable as a spark; something that trembles, as i do, between bliss and terror. let the more loving one be me, wh auden wrote in one of the greatest incitements to life in human history. to the rational mind, it is a ludicrous directive— rendering us at once totally bare and completely vulnerable to the certainty of loss. but to the fierce and foolish, it is perhaps the only reasonable retaliation to entropy.

Claudius Rudolf built the word entropy from the Ancient Greek tropē, or: transformation. we are accidental creatures of energy and time perpetually baring witness to the gradual undoing of our being: to the thermochemical collapse of our lives, our bodies, and our world into disorder and chaos in which the only certainty is loss.

this is the governing rule of our time: disorder. the dissolution of clarity, unknowns, the inevitable undoing of our every moment: that, as Edna St. Vincent Millay perfectly wrote, all of us, the “lovers and thinkers” will become “one with the dull, the indiscriminate dust.”

meanwhile: grass still waivers. the Moon rises, and the sun does too. there are jetties and swans and my lover will stand again in the frame of a door, tossing an orange as though in thoughtless conspiracy with the sun. soon his hands too will be made strange by time, and even stranger by the loss of memory. children will be read stories and somewhere, against all odds, strangers will fall in love. light will move on clear water. cruelty will occurs on unlikely roads but grace will also. that is to say: we will hold one another fast against entropy; against the certain departure of everything we know and the presence of everything we do not know know that will follow it.

what more could we ask of the world than for it to make certain its own fleeting? than for it to remind us every day of the brevity and sheer chance of our own existence— that nothing is ours forever, no matter our own affectionate protest against the odds? it makes of any love a foolish thing but a fierce one also— perhaps the only protest more necessary and more stubborn than death.

it is breathtaking: this extinction of ours.

Man letting go of bird so it can fly, Coskun Cokbulan

in her piece The Genesis of Blame, Anne Enright writes of how the english word naked began as erom: a Hebrew articulation of being stripped down, raw, vulnerable. it is not, at its core, an invitation or a seduction. the word does not traditionally carry any shadow of sex. instead, this nakedness is closer to being skinned, to standing without the cover of leaves or flesh— bare in the face of the vast indifference of the world to our brief and incidental lives.

as Enright writes:

“Called out by God, Adam says: ‘I heard you in the garden, and I was afraid because I was naked; so I hid.’

His nakedness, erom, merely implies vulnerability. Perhaps Adam and Eve hid from God not because they were suddenly prudish, nor because their disobedience had been found out, but because they realised their fragility and insignificance. They were exposed, not as sexual beings but as mortal ones.”

vulnerability— not desire. fragility— not shame. what if Adam and Eve disappeared into the trees not because they were caught in the act of knowing, but because they became suddenly aware of the contours of their own inevitable endings? not as sexual beings at all, but as mortal ones, suddenly aware of the transience of their own skin?

love takes on a peculiar weight when the time we share is suddenly finite. the natural instinct of self-preservation is to seek safety, but in the pursuit of what is most beautiful, there is rarely any safe investment. even zebra finches shun their most self-protective faculties so that they might dream to sing.

there is no safety in love. there is no guarantee that anything we touch won’t either leave a mark or take one— and anything worthwhile will almost always do both. to love at all is to step off the curb, to wander into the crosswalk with your eyes fixed somewhere in the middle distance, hoping the light just stays green long enough.

in the words of c.s. lewis:

“Love anything, and your heart will certainly be wrung and possibly be broken. If you want to make sure of keeping it intact, you must give your heart to no one, not even to an animal. Wrap it carefully round with hobbies and little luxuries; avoid all entanglements; lock it up safe in the casket or coffin of your selfishness. But in that casket — safe, dark, motionless, airless – it will change. It will not be broken; it will become unbreakable, impenetrable, irredeemable. The alternative to tragedy, or at least to the risk of tragedy, is damnation. The only place outside Heaven where you can be perfectly safe from all the dangers and perturbations of love is Hell.”

- c.s. lewis, the four loves

let the more loving one be me: a quiet directive, and perhaps also an unpopular one in our current age— an understanding that love is not an act of possession but rather one of play. the game? to expand the boundaries of one’s goodness in the face of absolute and unequivocal loss. it’s hopeless, after all. so just how far can you go?

there is a certain freedom to being the more loving one. to love without ego, without an instinct for self-preservation, is to abandon oneself to something luminous and terrifying, as a bird sleeps unprotected in order to dream of music.

i honour being the more loving one, knowing that my affection for the world isn’t in any way predicated upon its affection for me— for all it cares, i can go to hell.

i am not certain there is any more powerful propellant to my own goodness than the brief and startling realisation that everything is dying. it is why i would like to love with total impropriety: to look death in the eye without dignity or restraint, let the world become wrecked with love; leave the windows open to it. what can love offer us if not a reprieve from the decent, a passage into the totally undignified; a world in which we do not have to withdraw or withhold, to play aloof or measure our worth by how well we can play an arbitrary game of restraint? the great power of death, i am beginning to learn, lies not with the ease of what it takes, but with the complication of what it gives. that is to say: the discovery of our own capacity to for goodness.

to be the more loving one is a passage— a momentary reprieve from the decent, dignified world of restraint. and i can think of no greater ambition than this: to risk every safety for what is most volcanically tender: to be fully seen and wholly generous— blazing with a quiet ecstasy for this total accident of chance that is my life.

photographer unknown. two birds dreaming, perhaps.

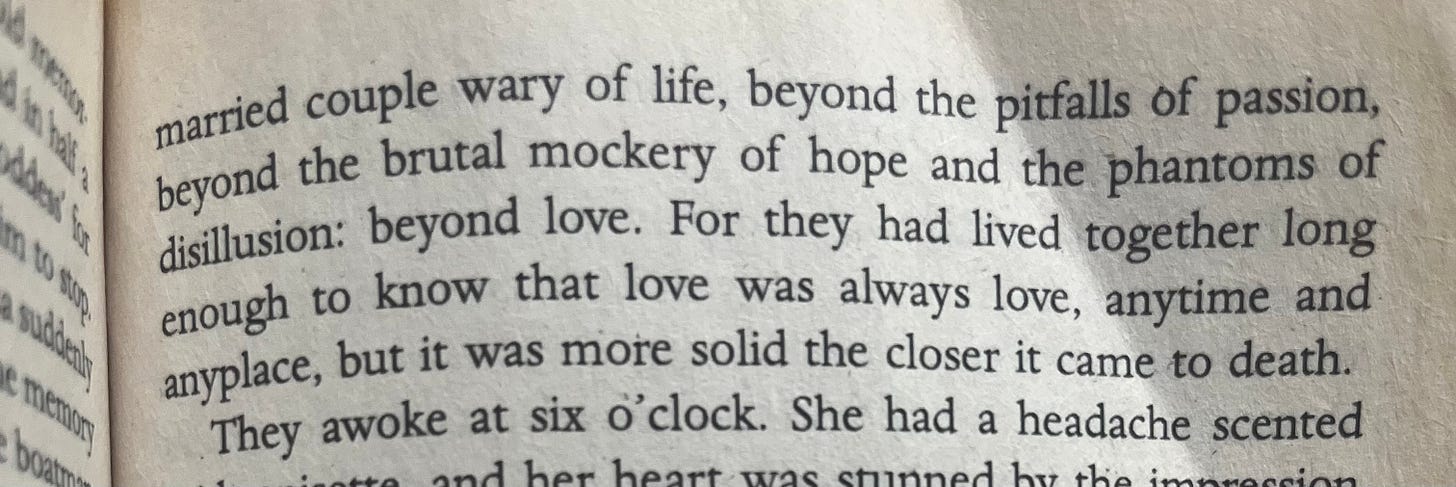

i recently reread marquez’s love in the time of cholera. there is a particular line toward the end, during Fermina and Fernando’s final passage across the river:

love was always love, anytime and anyplace, but it was more solid the closer it came to death.

excerpt from Love in the Time of Cholera, Gabriel Garcia Marquez.

i think of this often: this impossibility of abstracting our capacity for goodness from our own destiny as vulnerable, mortal creatures. but now, I think also of how love sharpens as it nears the edges of life. love is always love, anytime and anyplace, but it is more solid the closer it comes to death. to love as the end approaches is to love in high relief, stripped of our usual disguises.

what more can we ask for than for the opportunity to care for one another? to discover ourselves not by way of what we want, what we can earn or what we can achieve, but through our capacity for goodness?

if equal affection cannot be.

let the more loving one be me.

i think of that as a kind of music; a singing into the dark.

w.h. auden, having lived through a war that answered no prayers and saved no souls, made a single revision to his poem years later.

the line had originally been a plea— we must love one another or die— a call to arms against the inevitable, an insistence that love might somehow intervene in entropy. history, however, had rendered the line unbearable. eighty million lives lost made a mockery of his faith in language, in poetry, in anything resembling salvation.

years later, as if finally resigned to what the war had taught him, auden finally rewrote the line: we must love one another and die. a simple conjunction, a single word, but there it was—his acceptance that love is no antidote to death. it is its companion.

we must love one another and die. not because love saves us, but because an undignified love dignifies the brief time we have been given. there may be no safety, but there will be music. love is always love, anytime and anyplace, but it is more solid the closer it comes to death.

i say do it fiercely and give it foolishly.

love,

ars poetica.

little voice: it is my belief that Poetry is a human birthright. it is for this reason that my work will always be completely free, but it takes considerable Time and Love to give to you each week. if it has brought you something, please consider buying me a book so that I may continue to tuck Words in your pocket:

I heard a bird sing

In the dark of December

A magical thing

And sweet to remember.

“We are nearer to Spring

Than we were in September,”

I heard a bird sing

In the dark of December

Oliver Hereford

![POEM] To Be Alive by Gregory Orr : r/Poetry POEM] To Be Alive by Gregory Orr : r/Poetry](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F43861c64-1dca-4937-9158-1e744f4957c4_2921x2710.jpeg)

Thank you - these words are beautiful and ring with hope and challenge me to love and sing. I’m getting ready to take my father with advanced dementia to visit “the lady he loves and likes to visit”. “The lady” is in advanced stage of Alzheimer’s if she’s having a “good” day will slowly come around and light up and they lean towards each other smiling talking even laughing. He is so gentle and kind toward her. The staff thinks they are married - even though they met in memory care for a few months his psychiatry background was in full swing as he talked with her helped her eat gained her trust. She let him help her eat- he brings her chocolates every visit. Through all the changes in his brain what is there is love - love in action even when she doesn’t respond to him. He is tenacious. Today I’m bringing my drawing satchel and will draw the 2 of them together.

This is beautiful. It brought tears of fullness. Thank you! And the title alone a meditation: "keep no safe distance from alive." Sigh.. And we truly are like the finch, singing in dreams, intimate in this unfathomable love in aliveness - in life - now and now and now. Love was always love. Yes. Perhaps at times we just pretend to keep a distance, pretend to be smaller than such unspeakable beauty. Really, how can we move away from love, from reality's music, when intuitively we know we are that? Thank you for this beautiful writing.