dear little voice,

some say we come from the stars. others say we are slowly turning to dust.

me? i don’t know.

so i go for a walk.

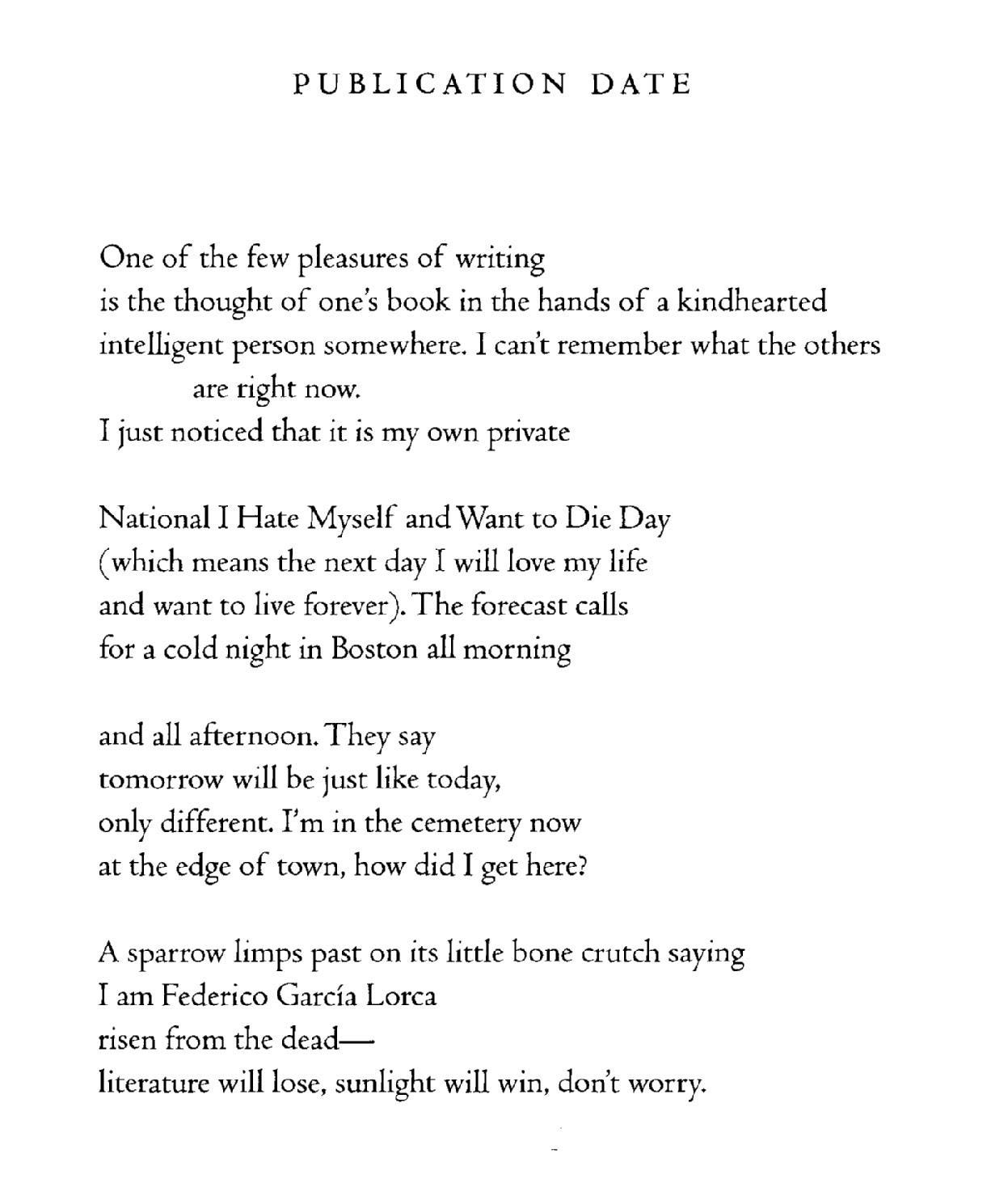

Publication Day, Franz Wright.

i have sat in fashionable rooms where the air felt heavy with conversation, the kind of talk that circles itself, idle yet insistent, as though to fill the space between the walls with proof of its own existence. i have watched artists cry over their legacies, watched them smuggle their self-absorption into the language of ambition, as if the terms of greatness could be negotiated by anyone willing to endure the requisite agony. i have seen them clamoring—not for language, not for truth, but for readers, for relevance, for some abstract notion of permanence. countless hours spent locked in the infinite internality of meditation, or looming over small books promising them talent, happiness, success, enlightenment.

there is a peculiar weight to becoming— whether it be becoming a marvellous artist, a significant person, a good person, or a presence that we decide makes us a person at all. it absorbs us, distracts us, entertains us, this endless accounting of what might just add up to mattering. but how unseemly it is— this focus on the apparatus of success: the audience, the patron, the status, the review. it will come, or it won’t. likely, it won’t. meanwhile: there is the light spilling through a window, the back of a butterfly’s wing, a tear caught in the act of drying, the knowledge that saturn exists. these things are here. so you are here.

Joy Harjo says it better: “poetry is not a career—you become poetry or are in a state of becoming with poetry.” the map is not linear, not a straight road but a series of arcs, overlapping and crisscrossed, bound by history, guided by memory. this is the shape of becoming, of noticing.

“Poetry is not a career— you become poetry or are in a state of becoming with poetry. My chronological map of becoming would not be linear, rather it has been crisscrossed with arcs of events, poems, poets, arts, music, all bound and directed by history and memory.”

- Joy Harjo, On Listening and Writing with Intention

The stone floor of a church in Brittany, France comes alive with color as morning sun filters through stained glass. photo: Jim Richardson

so, i have lost my fascination with ambition.

i have been wasting my time; making of it nothing but mere and earnest sentiment. i prefer whatever it is that makes the thing inside of me breathe quiet as a flame. i like long walks and apples and startling intrusions of beauty. i like to write letters to the people who need them. i press flowers in between the pages and slip them between the hinges of doors. i listen. i try to ask a question more unexpected than the one before. i leave poems on pillowcases and learn the different names for flowers. and i have realised that what i am in fact most ambitious about is to quietly push my love to the limits of itself, and then go further. so i call my grandmother. i fall in love and think ‘this is good work’. i look to my man and kiss him because we will die soon. we will and everyone else we love will too. and so i am walking around looking at them and loving them all too. and i am thinking about the beauty of the instinct in the wake of the thought– how grateful, how unworthy i am to one day die, and to know this too.

to live in this way—to accept that the act of creation is its own form of being—is both terrifying and liberating. it dismantles the lie that we must transcend our ordinary lives to make them worthwhile. instead, it asks us to turn toward the small, the fleeting, the luminous.

literature will lose.

sunlight will win.

don’t worry.

i learned recently that human beings glow: a secret shared among cells, too soft for the human eye.

in a study from 2009 performed by Masaki Kobayashi, Daisuke Kikuchi, and Hitoshi Okamura, five men were sealed in dark rooms and monitored with cameras so sensitive that they could detect light at the level of a single photon when kept at -120 degrees and sealed in a completely light-tight room. the men being filmed needed to be in complete darkness, as well as very naked and very clean.

the authors of the study concluded that we all ‘directly and rhythmically’ emit light, stating: ‘the human body literally glimmers. the intensity of the light emitted by the body is 1000 times lower than the sensitivity of our naked eyes.’ it is apparently our faces that shine brightest, especially around the cheeks and mouth, revealing the warmth of our breath, the quiet persistence of blood beneath skin and— perhaps to a romantic— words.

scientists will call it biophoton emission, but I think of it as something more gentle—a light we carry inside us as natural as breathing, a glow that comes and goes with the hours.

it’s a small study, of course, but it’s a startling and delicious thought: that amid the dimness, we are in fact, even if invisibly so, startlingly luminous beings.

Roman Vishniac. Sunlight streaming into a railway station. Berlin. 1920′s

in his collected essays, Ralph Waldo Emerson writes: “the question of Beauty takes us out of surfaces, to thinking of the foundations of things”. it is a line at once evocative of the philosopher Iris Murdoch’s notion of goodness— “an occasion for ‘unselfing”— a notion that also feels like a liberation from exteriors; a return to the foundations of things— perhaps away from literature, and toward sunlight.

in The Sovereignty of Good, she writes:

“The self, the place where we live, is a place of illusion. Goodness is connected with the attempt to see the unself, to see and to respond to the real world in the light of a virtuous consciousness. This is the non-metaphysical meaning of the idea of transcendence to which philosophers have so constantly resorted in their explanations of goodness. “Good is a transcendent reality” means that virtue is the attempt to pierce the veil of selfish consciousness and join the world as it really is. It is an empirical fact about human nature that this attempt cannot be entirely successful.”

‘Love is the extremely difficult realisation that something other than oneself is real. Love, and so art and morals, is the discovery of reality.’

the self, the place where we live, is a place of illusion.

goodness, for Murdoch, is not about escaping the self but expanding beyond it, not a retreat but a movement outward—a sort of reaching. she called it an act of love: love is the extremely difficult realization that something other than oneself is real. this is not an abstract concept. it’s the earth underfoot, the weight of another’s hand in yours, a thread of sunlight enflaming the grass.

to see the world as it is, she argued, is to love it well.

we are luminous beings.

photo: Masaki Kobayashi, Daisuke Kikuchi, and Hitoshi Okamura.

text: Roland Barthes, A Lovers Discourse

this is not an easy clarity. the self clings tightly; it resists unmaking. to unself is an act of attention, she said, a willingness to step aside from your own smallness long enough to see the vastness of the real. this is not glamorous work. it is slow and it is persistent.

There is a gold light in certain old paintings,” Donald Justice.

like Plato before her, Murdoch saw goodness as a kind of truth-seeking, a relentless turning toward reality. she believed that realism in art was a moral achievement, a way of seeing that required humility, discipline, and love. to see life clearly is to pierce through distraction, through noise and self-obsession, and to touch what is real. to see something clearly means to let go of the comforting fiction that the self is at the centre of things. it means surrendering to the fact that the world goes on, indifferent to our attention. but when we insist on it—when we stop, and look, and truly see—there’s a kind of grace made suddenly and intrusively available to us— and peace, too. it is, as Murdoch writes, an act of love.

it may very well be that the only thing we are here to do is what the body does naturally: emit light.

reading Whitman, i am struck by the line: “the whole theory of the universe is directed unerringly at a single individual, namely, you”.

it feels somehow essential to our condition that he is correct: that this existence, with its noise and chaos, its vastness and its silence, is somehow focused entirely on us. yet that same truth feels unbearable, as if the weight of it might crush us under its influence.

Murdoch adds to this a softer clarity: that all personal love—fragile, imperfect, and painfully specific—is only a fragment of some larger, unnameable force. some stories call this force God. others call it Poetry. Dante called it “the Love that moves the Sun and the other stars.” i can only think of it as a kind of light— the luminosity that continues to ripple off of us, that insists on touching others, that continues to reach into the world, even when there is nothing to hold on to. Jeanette Winterson called this the paradox of art, but it’s also the paradox of living: to yield to something you cannot fully understand and to give yourself over to it entirely, even when the contours of it are unknowable.

no act of surrender is comfortable, and this one in particular asks us to see the universe not as a stage for our assertions or a theory to be solved, but as an act to be lived—a way of dissolving into the vastness of things, of loving not as an act possession, but of participation.

if these small lives we have been given are not merely a fragment of something larger but the whole itself, then perhaps our only real task is to live as the whole: not to assert, or conquer, or even to achieve goodness, but to see. to do what the body does without knowledge, pretense, or request: to emit light.

it is a quiet truth, and a difficult one, but it feels like the only one. to love as if this world, in all its strangeness and impermanence, were enough. to exist not as the centre but as the infinite— which like light cannot inhabit a centre of virtue of being everywhere, always. not by holding onm but by letting go.

and if these small lives we have been given are not just a fragment but somehow the whole—then perhaps our only real task is the task of light: to learn how to touch one another, and in what places, so as to make visible to one another what we may not know is there.

Kahlil Gibran, excerpts from Sand and Foam [ID in ALT]

i often wonder why a small life is always read as a terrible life. it is testament to an insular condition that human beings could be so grandiose as to believe that our lives, birthed in the shadows of stars, the coolness of a moon, the warmth of a sun, and an entire universe to live in, are small.

some say we come from the stars. others say we are slowly turning to dust.

me? i have lost my fascination with ambition.

so i go for a walk.

literature will lose.

sunlight will win.

don’t worry.

love,

ars poetica.

little voice: it is my belief that Poetry is a human birthright. it is for this reason that my work will always be completely free, but it takes considerable Time and Love to give to you each week. if it has brought you something, please consider buying me a book so that I may continue to tuck Words in your pocket:

Ritual Is Journey, Chris Abani

I just spent 20 minutes trying to express my appreciation for your writings, discovered just this morning. I actually had a rather long paragraph addressing my brief spark of connection with your words and your gleanings. I tend to be a sharer as well as a hoarder, wanting to share my discoveries of beauty with those around me, only to be met with harumphs and eyes filled with-"what the hell is he talking about-again?" contrasted with my desire to collect and save and safeguard "spark worthy" findings in folders, fancy bottles, canning jars, and boxes. Only to be burdened with thoughts of: "Why did I share that?" and a myriad of clutter filled receptacles that I will someday re-visit. I forget the full content of my original paragraph (was lost by hitting an errant key) but it had something to do with the one you see here.

Ecological thought includes a branch called Deep Ecology which recognizes the ego-self, the social-self, and the ecological-self.